Microencapsulation of Mitragyna leaf extracts to be used as a bioactive compound source to enhance in vitro fermentation characteristics and microbial dynamics

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Mitragyna speciosa Korth is traditionally used in Thailand. They have a high level of antioxidant capacities and bioactive compounds, the potential to modulate rumen fermentation and decrease methane production. The aim of the study was to investigate the different levels of microencapsulated-Mitragyna leaves extracts (MMLE) supplementation on nutrient degradability, rumen ecology, microbial dynamics, and methane production in an in vitro study.

Methods

A completely randomized design was used to assign the experimental treatments, MMLE was supplemented at 0%, 4%, 6%, and 8% of the total dry matter (DM) substrate.

Results

The addition of MMLE significantly increased in vitro dry matter degradability both at 12, 24, and 48 h, while ammonia-nitrogen (NH3-N) concentration was improved with MMLE supplementation. The MMLE had the greatest propionate and total volatile fatty acid production when added with 6% of total DM substrate, while decreased the methane production (12, 24, and 48 h). Furthermore, the microbial population of cellulolytic bacteria and Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens were increased, whilst Methanobacteriales was decreased with MMLE feeding.

Conclusion

The results indicated that MMLE could be a potential alternative plant-based bioactive compound supplement to be used as ruminant feed additives.

INTRODUCTION

Tropical plants are rich in bioactive compounds (BC) namely phenolic, flavonoid compounds, and antioxidant capacities [1,2], which may have anti-microbial effects, especially in methanogen and protozoal populations, and which improve the characteristics of rumen fermentation [3,4]. The BC have been demonstrated to influence product quality and health condition that play a vital role in animal nutrition [5].

One of the alternative sources of plants containing BC is Mitragyna speciosa Korth, a tropical plant in Southeast Asia including Myanmar, Malaysia, and Thailand [6]. M. speciosa is popularly known as Kratom in Thailand. They are traditionally used to treat tiredness, opioid addiction, and relieve pain [7]. The leaves of M. speciosa have shown the presence of BC such as flavonoids, alkaloids, glycoside, and triterpenoids [8]. This plant has been demonstrated to have several pharmacological properties such as antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant [9]. Accordingly, Phesatcha et al [10] reported that the Mitragyna leaf powder supplementation as a BC can improve rumen fermentation, whilst decrease rumen protozoa, and methane production. Chanjula et al [11] revealed that Mitragyna leaf powder enhanced rumen ecology by increasing nutrient digestibility, volatile fatty acid (VFA, propionic acid profile), and reducing methane production in goats.

Microencapsulation is an emerging technology that is commonly used nowadays in animal nutrition for the preparation of stable products (vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, as well as BC) [12]. This technique can act as a physical barrier to protect pharmaceuticals from harsh external environment, which increases the stability of the substance [13]. Among microencapsulation procedures, spray-drying is a practical approach that could produce a constant microcapsule [14]. However, no previous research has evaluated protection of BC by microencapsulation technique of Mitragyna leaves as a strategy to enhance their interactions with ruminal fermentation. Therefore, this study aimed at testing the susceptibility of microencapsulated BC from Mitragyna leaves to in vitro nutrient degradation, rumen ecology, and microbial diversity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal ethics

The collection of rumen fluid from Thai-crossbred dairy cows was permitted by the Institute of Animals for Scientific Purpose Development (IAD), Thailand (number U1-06878-2560).

Microencapsulated-Mitragyna leaves extracts preparation

The plant sources were harvested at Rajamangala University of Technology Srivijaya (MUTSV), Nakhon Si Thammarat, Thailand. Fresh Mitragyna leaf was dried at 60°C. The dried Mitragyna was ground through a sieve opening of 1 mm (Cyclotech Mill, Tecator, Hoganas, Sweden). The powder was mixed with water and heated in a Microwave to 60°C, and after 35 minutes the particulates filtered out. The liquids were combined with tween 80 and chitosan [15], and they were spray-dried microencapsulated-Mitragyna leaves extracts (MMLE) by using Bǚchi B-191 Mini Spray Dryer [16]. The surface morphology of MMLE was observed using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM; model: Mira, Tescan Co., Brno, Czech Republic) according to Ko et al [17]. MMLE were chemically analyzed for dry matter (DM; number 967.03), ash (number 942.05), and crude protein (CP; number 984.13) following the methods of AOAC [18], as shown in number 973.18. Fiber fractions (neutral-detergent fiber [NDF] and acid-detergent fiber [ADF]) were determined using Ankom A200i Fibre Analyser (Ankom Technology Co., New York, USA); according to Van Soest et al [19]. MMLE were analyzed for BC especially total phenolic compound (TPC) using Folin–Ciocalteu reagent by absorbance at 765 nm [20] and total flavonoid compound (TFC) following the method of Topçu et al [21], based on colorimetric changes with a 10% aluminum chloride solution read at 415 nm. Moreover, the sample was analyzed the antioxidant capacities including 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) [22], 2, 2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) [23], and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) [24], which are additional explained in Phupaboon et al [25].

Experimental design and treatments

The study was assigned in a completely randomized design (CRD). Total dietary substrates (the ratio of rice straw to concentrate at 60:40) were weighed at 0.5 g into the 60 mL bottles, then the treatments were supplemented with MMLE at 0%, 4%, 6%, and 8% of total DM substrate, respectively.

Rumen fluid collection and preparation

The rumen fluid donors were four Thai-crossbred dairy cows (body weight, 400±10 kg). The animals consumed total mixed ration twice daily at 7:00 and 16:00 o’clock, and they had unlimited access to mineral block and clean water for at least 14 days following the National Research Council (NRC) [26] requirement for dairy cows. Samples of the rumen fluid were taken using a tube connected with a vacuum pump set through the mouth to the middle of the rumen and into a plastic flask. The samples were transferred into a bottle with thermal insulation at 39°C after being filtered through four layers of folded cheesecloth. Part of the preparation of the medium solution (2,000 mL) contains 0.24 mL of micro-mineral solution, 2.44 mL of resazurine, 99.0 mL of reduction solution, 480.0 mL of macro-mineral solution, 480.0 mL of buffer solution, and 950.0 mL of distilled water, respectively. Under constant CO2 flushing, rumen fluid was combined with the medium substrate at 1:2 (mL/mL). Substrates in total (concentrate and roughage sources) were weighed into glass bottles (60 mL), then the respective treatments, MMLE was added at 0.00, 0.02, 0.03, and 0.04 g DM. The bottles were capped with rubber stoppers and aluminum caps. Rumen inocula mixture was added (40 mL) to the bottles and incubated at 39°C, as described in Matra et al [27].

In vitro incubation

During incubation, the production of gas was recorded at 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h (3 bottles/treatment). The equation of Ørskov and McDonald [28] was used to analyze all gas production data; Y = a+b (1−e−ct), where Y = gas generated at time “t” (mL), a = the gas production from the immediately soluble fraction (mL), b = the gas production from the insoluble fraction (mL), c = the gas production rate constant for the insoluble fraction (mL/h), and t = incubation time (h). The samples were collected separately for pH, microbial population, ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N), and VFA analyses at 12, 24, and 48 h-after incubation (2 bottles/treatment). A portable pH meter was used to determine the pH (HANNA Instruments HI 8424 microcomputer, Singapore). The rumen fluid instances were centrifuged at 16,000×g for 15 minutes after being filtered through instances cheesecloth, then to analyze the NH3-N concentration using micro-Kjeldahl techniques, the supernatant was kept at −20°C [18] and VFA profiles (HPLC; ETL Testing Laboratory, Inc., Cortland, NY, USA); according to Samuel et al [29]. Additionally, in vitro nutrient degradability was measured using a different set (2 bottles/treatment). The production of methane (CH4; 3 bottles/treatment) was measured using GC machine (GC-2014; Shimadzu Co Ltd., Kyoto, Japan); methane production (% v/v) = (Peak area/18,108)/0.3, where 0.3 = the volume of gas was kept in the bottle (10 mL) and 18,108 = the slope estimates of the standard methane graph.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

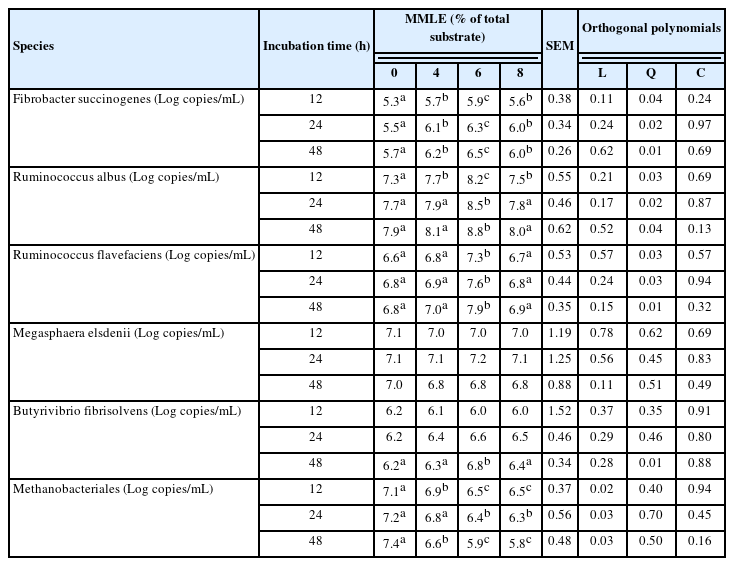

Approximately, 1 mL of rumen fluid from in vitro study was extracted for total genomic DNA (gDNA) following to the method of QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The gDNA quality (the concentration at ≥50 ng/μL) was indicated by absorbance at OD260/280 = 1.8 to 2.0 using Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). The microbial population including Ruminococcus albus, Ruminococcus flavefaciens, Fibrobactor succinnogenes, Butyribrivio fibrisolvens, Megasphaera elsdenii, and Methanobacteriales were identified using the specific primers through real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique, as shown in Table 1. The real-time PCR amplification and detection were performed by Maxima SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix using Chromo 4TM system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), more detail of the protocols was demonstrated in Koike and Kobayashi [30].

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the general linear model procedure following to the method of SAS [34], for a CRD; Yij = μ+τi+ɛij, where μ = overall mean, τi = treatment effect, ɛij = residual error, and Yij = observation. The mean values of the experimental treatments were compared with Tukey’s test. Differences between treatment means were reported as statistically different had p-values of <0.05 and <0.01. Trends of MMLE supplementation responses were analyzed by Orthogonal polynomials.

RESULTS

Nutritive values and morphological characterization of MMLE

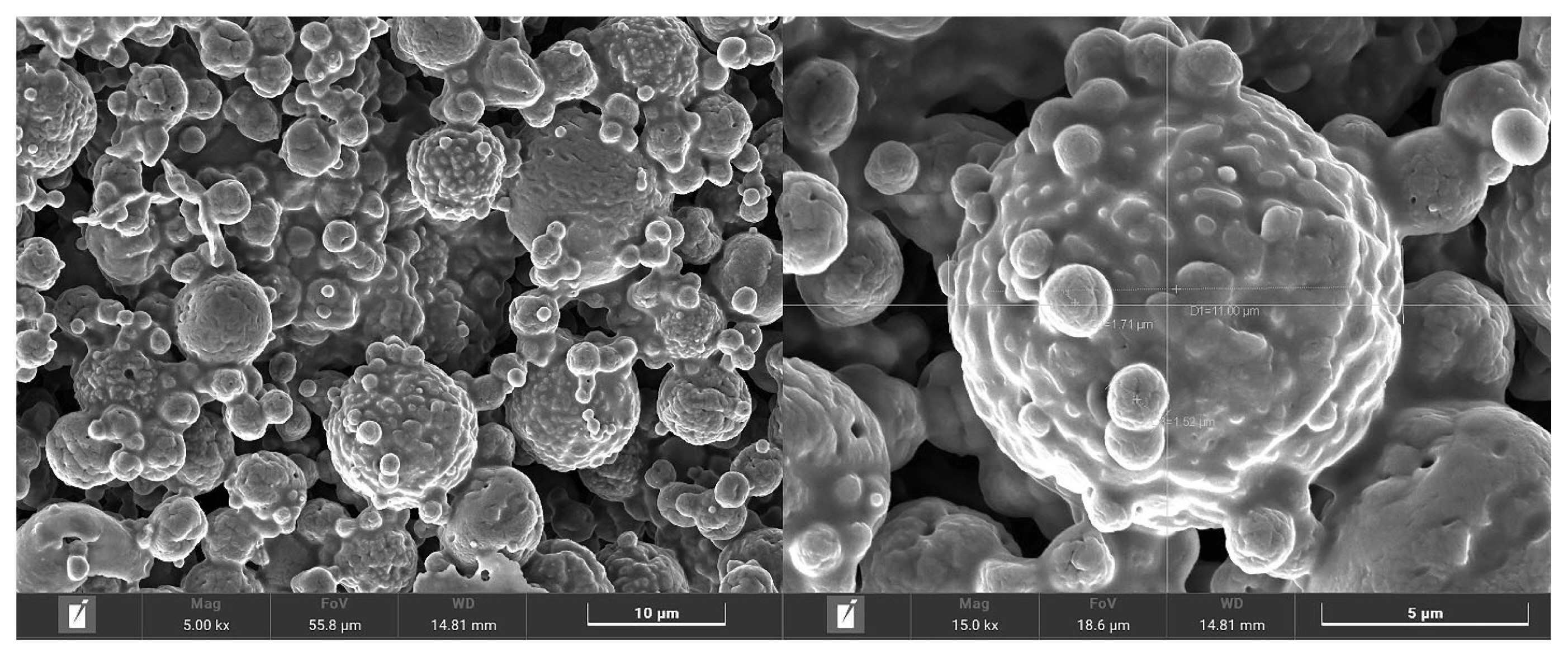

The nutritive values of MMLE were 90.1% DM, and 96.4%, 18.6%, 72.2%, and 21.9% DM basis for OM, CP, NDF, and ADF, respectively. Importantly, BC contained in MMLE were 307.8 mg gallic acid equivalent/g DM of TPC and 105.3 mg quercetin equivalent/g DM of TFC. In the antioxidant capacity, including 94.8% DPPH, 90.3% ABTS, and 34.4 mg trolox equivalent/g DM of FRAP), as shown in Table 2. Moreover, morphological characterization of MMLE, chitosan microparticles showed that they had entirely spherical surface morphologies, with porous surrounding particle spheres interspersed with smooth and rough surfaces. The MMLE identified numerous particles with sizes ranging from 1.5 to 11.0 μm in diameter (Figure 1).

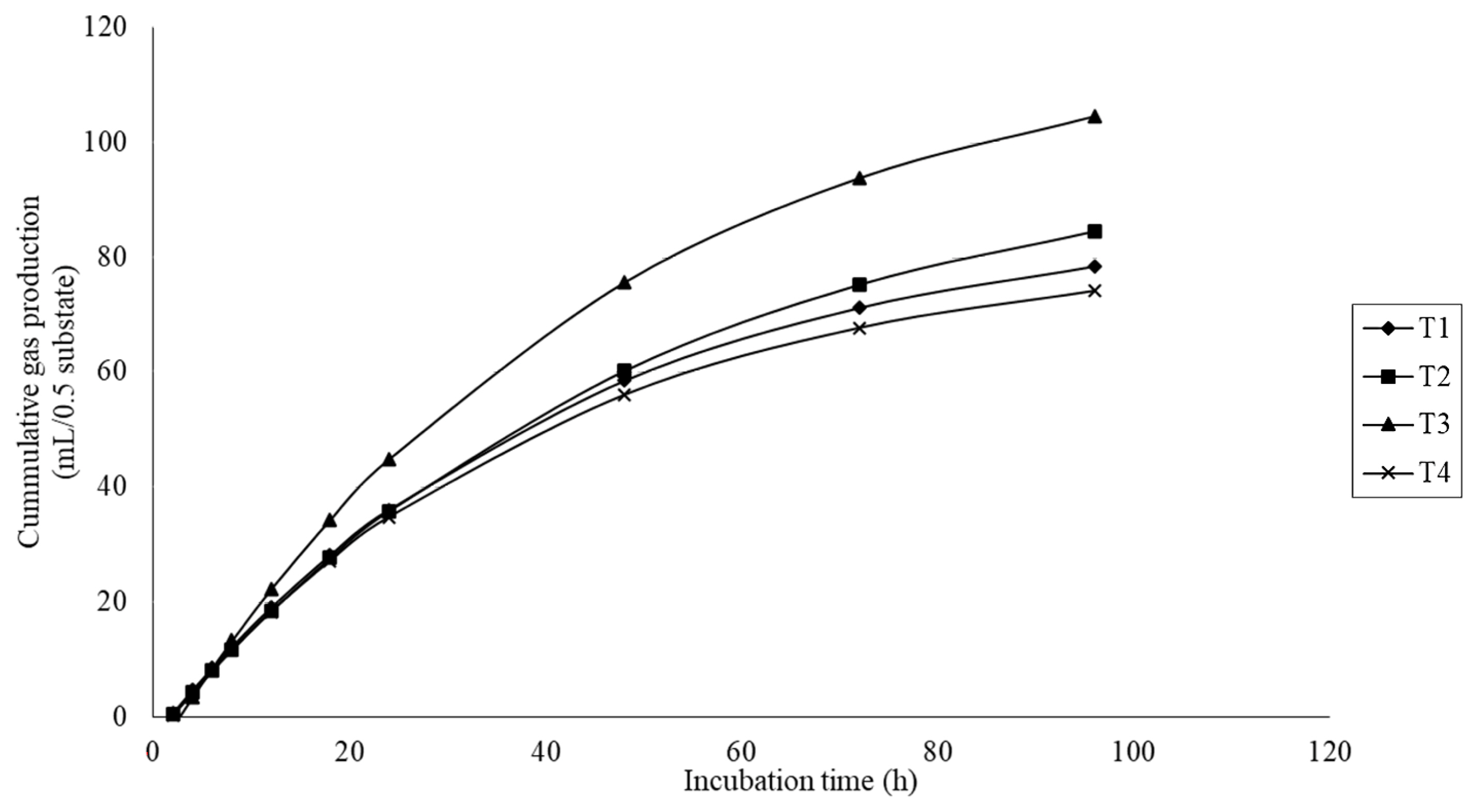

In vitro gas production kinetics

The gas production results are presented in Table 3. Gas production kinetics, including the gas production from the immediately soluble fraction (a), the potential extent of gas production (a+b), and the gas production from the insoluble fraction (b) were significantly different (quadratic effect; p<0.01) with MMLE supplementation. There was a significant difference (p<0.05) on the gas production rate constant for the insoluble fraction (c), with higher values for the treatment fed 6% MMLE. In addition, the cumulative gas production was quadratically increased (p<0.01) with MMLE addition (Figure 2).

Supplementation of microencapsulated-Mitragyna leaves extracts on gas kinetics and nutrient degradability

Nutrient degradability

The MMLE had the greatest in vitro dry matter degradability (IVDMD) (p<0.05) at 12, 24, and 48 h of fermentation (quadratic effect) when supplemented with 6% of total DM substrate. The lowest IVDMD occurred with MMLE addition at 8% of total DM substrate. Furthermore, this parameter was not linearly influenced, as presented in Table 3.

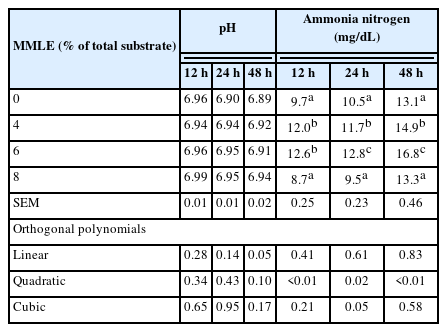

Ruminal pH and NH3-N concentration

Table 4, the ruminal pH (12, 24, and 48 h) were not affected (p>0.05), when increasing the level of MMLE. The ammonia nitrogen content (24 and 48 h) was quadratically increased (p<0.05 and p<0.01) when MMLE was added at 6% of total DM substrate. This concentration at 24 and 48 h was significantly higher (p<0.05 and p<0.01) than at 12 h by the supplementation of MMLE.

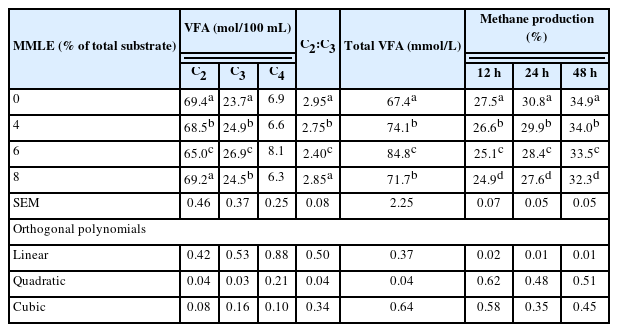

Volatile fatty acids and methane production

The 6% MMLE had significantly (quadratic effect; p<0.05) greater acetate, propionate, acetate to propionate ratio, and total VFA production, and it had the highest propionate content (p<0.05) when compared with the control treatments. The content of butyrate did not differ (p>0.05) with MMLE addition. Moreover, methane production (after 12, 24, and 48 h of fermentation) was linearly decreased (p<0.05) when MMLE level was increased. The supplementation of 6% MMLE had the lowest methane content (p<0.05) compared with other treatments, as shown in Table 5.

Microbial dynamics

Based on species level, MMLE supplementation was able to change the bacterial and archaeal population. The present findings showed that MMLE supplementation increased cellulolytic bacteria, namely Ruminococcus albus (p<0.05), Ruminococcus flavefaciens (p<0.05), and Fibrobactor succinnogenes (p<0.05). The relative abundance of Butyribrivio fibrisolvens increased (p<0.05) in 6% MMLE compared with control, while Megasphaera elsdenii was not statistically different (p>0.05) among treatments. Importantly, Methanobacteriales was linearly decreased (p<0.05) when fed the MMLE (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

In vitro gas production kinetics

In the present study, gas kinetics, especially the gas production rate constant for the insoluble fraction (c), were improved by the MMLE supplementation. It could be due to the capability of BC to enhance microbial growth and activity and its ability to bind in the contents of protein and fiber [3,35]. Accordingly, Phesatcha et al [10] stated that Mitragyna leaves powder enhanced gas production kinetics, it’s possible that it improved the rumen microbe and increased the substrate’s capacity to degrade, so improving the kinetics of gas production.

Nutrient degradability

The MMLE supplementation to the diet clearly increased IVDMD, which was significantly higher with the addition of 6% of total DM substrate. This might be explained by an increase in the number of microbes, which would cause more feed to breakdown, which was one important role of the BC contained in MMLE. Zhan et al [36] explained that flavonoids and phenolics have a range of biological effects that can impact ruminal microbes, which in turn increases how feed is degraded in the rumen. Sommai et al [37] reported that flavonoid extracts from Alternanthera sissoo supplementation significantly increased in vitro degradability.

Ruminal pH and NH3-N concentration

This research has shown that ruminal pH did not influence the treatments. For typical rumen fermentation, microbial growth, and microbial activity, the data were in the normal range (6.85 to 6.99). Accordingly, Wanapat [38] reported that pH ranges between 6.5 and 7.0 are optimum for microbial activity and growth. Strategic addition of phenolic-containing feedstuffs can enhance rumen fermentation by preserving a higher pH [39]. Furthermore, MMLE supplementation was improved NH3-N concentration both 12, 24, and 48 h. This may be a result of the plant-bioactive extract’s potential to enhance the proteolysis process. Plant-based bioactive supplementation increases the concentration of ruminal NH3-N, which was confirmed by Ahmed et al [40]. Furthermore, it could be a positive effect of the concentrate and MMLE containing protein source at 14.6% and 18.6% CP, thus increasing the amount of NH3-N present as a result.

Volatile fatty acids and methane production

Under this investigation, MMLE supplementation increased the molarity of VFAs especially propionate and total VFA production, while decreased acetate production. Patra and Saxena [41] explained that BC may also cause a change in propionate produced when there is an excess of hydrogen. Hydrogen is used to create propionate instead of being the major substrate for the methane production pathway [42]. These findings agree with Totakul et al [43] who revealed that the Cnidoscolus leaves pellet supplementation significantly increased propionate concentration, while decreased acetate to propionate ratio. Propionate content typically increases when rumen methanogenesis is inhibited, and this was also shown in the current investigation. Bodas et al [44] demonstrated that phenolic acids and polyphenols suppress methanogenesis, while also improving fermentation parameters. Therefore, phenolics and flavonoids from multi-functional tropical plants have the potential to directly inhibit methanogen population and activity. Furthermore, BC in feeds has been demonstrated, whether in natural form or as plant extracts, to have an impact on the rumen’s ability to reduce methane production by rumen microorganisms. Cellulolytic bacteria are among the specific microorganisms that BC directly affects. It causes F. succinogenes (the non-hydrogen producing bacteria) to produce more propionate and reduce the acetate to propionate ratio [45]. In this study, MMLE supplementation clearly decreased methane production. As described in Chanjula et al [11], dried Mitragyna leaves linearly decreased methane production and F. succinogenes quadratically increased when the level of Mitragyna leaves was added. Huang et al [46] showed that Paulownia hybrid leaves decreased methane production, it could be the result of a decline in Archaea especially methanogens due to secondary metabolite activities.

Microbial dynamics

In the current study, the cellulolytic bacteria population increased with the levels of MMLE supplementation. Consequently, the phenolic and flavonoid containing in MMLE, compounds could influence the cellulolytic bacteria activities especially when MMLE was supplemented at 8% of total DM substrate. BC activity alters protein translocation, phosphorylation processes, ion gradients, electron transport, and other enzyme-dependent processes, which results in the impacted cellulolytic bacteria losing chemiosmotic control [47]. Nevertheless, BC should be supplemented at a suitable level for microbe activity, especially cellulolytic bacteria. F. succinogenes, R. albus, and R. flavefaciens have been identified as the main cellulolytic bacterial species in the rumen and more these groups could improve ruminant degradation of fiber [48]. According to Chanjula et al [11] stated that dried Mitragyna leaves was enhanced F. succinogenes, R. albus, and R. flavefaciens. Huang et al [46] revealed that Paulownia hybrid leaves containing flavonoid and phenolic compounds increases total bacteria, as well as in particular species of B. fibrisolvens and F. succinogenes. This may be explained by the ruminal microbes’ response to the flavonoids and phenolics, perhaps as a result of hydrogenation, which transforms toxic compounds into less toxic forms [49]. Moreover, MMLE addition increased Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens group, while reduced methanogens group (Methanobacteriales), which could be attributed to the availability of BC in the MMLE. Similarly, Phesatcha et al [10] showed that the supplementation of Mitragyna leaves reduced ruminal methanogens population and methane production. BC has an immediate impact on rumen methanogens, by interacting with the proteinaceous adhesin, suppressing methanogen growth, reducing interspecies hydrogen transfer, and inhibiting the methanogen-protozoa complex’s formation [50].

CONCLUSION

Based on the findings, supplementation of MMLE at 6% of total DM substrate enhanced rumen nutrient degradability, fermentation end-products especially propionate production, and decreased methanogens and methane production. Hence, MMLE could be an effective dietary BC and could have the potential to be used for ruminant feed additives.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge their appreciation to the Tropical Feed Resources Research and Development Center (TROFREC), Department of Animal Science, Faculty of Agriculture, Khon Kaen University, Thailand.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.

FUNDING

The Fundamental Fund (FF) (grant number 65A103000130), Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research, and Innovation (MHESI) and Khon Kaen University Thailand kindly allocated funding for this study.