Effects of Dietary Garlic Extracts on Whole Body Amino Acid and Fatty Acid Composition, Muscle Free Amino Acid Profiles and Blood Plasma Changes in Juvenile Sterlet Sturgeon, Acipenser ruthenus

Article information

Abstract

A series of studies were carried out to investigate the supplemental effects of dietary garlic extracts (GE) on whole body amino acids, whole body and muscle free amino acids, fatty acid composition and blood plasma changes in 6 month old juvenile sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus). In the first experiment, fish with an average body weight of 59.6 g were randomly allotted to each of 10 tanks (two groups of five replicates, 20 fish/tank) and fed diets with (0.5%) or without (control) GE respectively, at the level of 2% of fish body weight per day for 5 wks. Whole body amino acid composition between the GE and control groups were not different (p>0.05). Among free amino acids in muscle, L-glutamic acid, L-alanine, L-valine, L-leucine and L-phenylalanine were significantly (p<0.05) higher in GE than in control. However, total whole body free amino acids were significantly lower in GE than in control (p<0.05). GE group showed higher EPA (C22:6n3) and DHA (C22:5n3) in their whole body than the other group (p<0.05). In the second experiment, the effects of dietary garlic extracts on blood plasma changes were investigated using 6 month old juvenile sterlet sturgeon averaging 56.5 g. Fish were randomly allotted to each of 2 tanks (300 fish/tank) and fed diets with (0.5%) or without (control) GE respectively, at the rate of 2% of body weight per day for 23 d. At the end of the feeding trial, blood was taken from the tail vein (n = 5, per group) at 1, 12, and 24 h after feeding, respectively. Blood plasma glucose, insulin and the other serological characteristics were also measured to assess postprandial status of the fish. Plasma glucose concentrations (mg/dl) between two groups (GE vs control) were significantly (p< 0.05) different at 1 (50.8 vs 62.4) and 24 h (57.6 vs 73.6) after feeding, respectively, while no significant difference (p>0.05) were noticed at 12 h (74.6 vs 73.0). Plasma insulin concentrations (μIU/ml) between the two groups were significantly (p<0.05) different at 1 (10.56 vs 5.06) and 24 h (32.56 vs 2.96) after feeding. The present results suggested that dietary garlic extracts could increase dietary glucose utilization through the insulin secretion, which result in improved fish body quality and feed utilization by juvenile sterlet sturgeon.

INTRODUCTION

Sturgeon is one of the oldest species of living vertebrates and often described as “living fossils”, with records dating back more than 150 million years. Today, the sturgeon is recognized as one of the world’s most precious commercial fish, mainly prized for its caviar, but increasingly also for its meat and as an ornamental fish (Mims et al., 2000). Most sturgeon species are bottom dwellers and feed benthically on insect larvae and small fish (Hochleithner and Gessner, 1999). In Korea, sturgeon aquaculture has begun in 1996 with the main species for sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), Siberian (A. baeri), Russian (A. gueldenstaedti), stellate (A. stellatus) and hybrid called bester (beluga female×sterlet male).

One of the commonest interests in fish farming worldwide is how to diminish production cost and extend outputs in the shortest time. One method is to include new substances into fish diets to improve feed conversion efficiency or elevate general conditions for fish growth and maintenance (Fernández-Navarro et al., 2006). Plant products have been reported to promote various activities like antistress, growth promotion, appetite stimulation and immunostimulation in aquaculture practices (Citarasu et al., 2001, 2002; Sivaram et al., 2004). Garlic (Allium sativum) is a perennial bulb-forming plant that belongs to the genus Allium in the family Liliaceae. Garlic has been used for centuries as a flavouring agent, traditional medicine, and a functional food to enhance physical and mental health. Dietary garlic decreases blood glucose by increasing the level of serum insulin (Ahmed and Sharma, 1997) and the S-allylcysteine sulfoxide present in garlic is responsible for its hypoglycaemic activity (Sheela and Augusti, 1992). Dietary garlic as a growth promoter in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) improved body weight gain, feed intake and feed efficiency (Diab et al., 2002; Shalaby et al., 2006). Our previous research suggested dietary garlic for juvenile sterlet sturgeon (60 to 100 g) could positively affect growth performance (Lee et al., 2008, Lee et al., 2012). But, no trial was conducted to study the effect of dietary garlic extracts on meat quality and metabolic effects of blood plasma for sterlet sturgeon till date. Therefore, this study was designed to investigate the effects of garlic extracts on whole body amino acids and fatty acids composition, as well as blood plasma changes of the fish.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of garlic extract

Two kg of garlic (Allium satium) powders obtained from the local market in Gyeonggi Province, Korea were left during 48 h in 99% ethanol 20 L (10% w/v) at room temperature (20±2°C), and the resulting extract was concentrated to 300 ml using rotary evaporator (DPE 1210 NE Series, EYELA. Japan), giving the extract of 6.7 g of garlic powder/ml. This extract was sprayed on the diet after dilution in 300 ml of distilled water.

Experimental design and diets

Juvenile sterlet sturgeons (Acipenser ruthenus) were obtained from Gyeonggi Province Freshwater Fisheries Research Institute, Gyeonggido, Korea. The first experiment was carried out to investigate the supplemental effect of dietary GE on whole body amino acid and fatty acid composition of juvenile sterlet sturgeon with average body weight 59.6 g. For which, two hundred fish selected from 2,000 fish were randomly allotted to each of 10 tanks (two groups of five replicates, 20 fish/tank). Fish were cultured in semi-recirculation freshwater system. Water temperature and dissolved oxygen levels were kept at 22±1°C and over 6 mg O2 L−1, respectively. Flow rate was adjusted at a minimum of 3 L min−1. A commercial extruded pellet of 1.7 mm size (Cargil Agri Purina Inc., Korea) was used as the experimental diet. The diets were prepared to contain 0% GE (Control) and 0.5% GE (diet 20 kg+100 ml garlic extract+300 ml distilled water) garlic extract. The mixture of garlic extract and distilled water was sprayed on the experimental diets, which were then dried in a dryer (GCT-104OR-4G, Fresh and Cool Technology Ltd., Korea) at 30°C for 48 h in order to volatilize remaining ethanol. The commercial diet was chemically analyzed to contain moisture 9.2%, crude protein 47.8%, crude fat 8.9% and crude ash 8.8%. Chemical composition of GE diet was analyzed to be same (moisture 9.6%, crude protein 47.6%, crude fat 8.7% and crude ash 8.8%). Five replicate groups of fish were fed the experimental diets by hand at the rate of 2% of fish body weight per day at 08:00 h, 13:00 h and 18:00 h, for 5 wks.

The second trial was carried out to investigate the supplemental effect of dietary GE on blood plasma changes of 6 month old juvenile sterlet sturgeon averaging 56.5 g. Fish were cultured in running freshwater system in which water temperature and dissolved oxygen were maintained at 21±1°C and over 7 mg O2 L−1, respectively. Flow rate was adjusted at a minimum of 100 L min−1. Fish were randomly allotted to each of 2 tanks (300 fish/tank, tank size, ∮4×0.6 m). Same diets used in the first experiment were employed. Diets were fed by hand at the rate of 2% of body weight per day at 08:00 h, 13:00 h and 18:00 h, respectively for 23 days.

Sample collection and analysis

At the end of the first trial, fish were anesthetized with AQUI-S (New Zealand Ltd., NZ) and then all fish in each tank were individually weighed and each five fish from each replication of two groups were selected at equivalent weight to analyze whole body amino acid and fatty acid composition, respectively. Each five fish from each replication of two groups were selected at equivalent weight to analyze free amino acid profiles of dorsal muscle. Blood samples were obtained from the caudal vessels with a heparinized syringe from each five fish of two groups after fish were starved for 24 h and anesthetized with AQUI-S. Hematocrit (PCV) and hemoglobin (Hb) were measured with the same fish by the microhematocrit method (Brown, 1980) and the cyan-methemoglobin procedure using Drabkins solution, respectively. Hb standard prepared from human blood (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, Missoruri) was used. The amino acids and free amino acids were quantified by the amino acid analyzer S433 (Syknm, Germany) using ninhydrin method. Analysis conditions were as follows: column size, 4 mm×150 mm; absorbance, 570 nm and 440 nm; reagent flow rate, 0.25 ml/min; buffer flow rate, 0.45 ml/min; reactor temperature, 120°C and reactor size, 15 m. Fish were stored at −20°C until analysis. Fatty acid methyl esters were obtained by direct transesterification (Metclfe et al., 1996) and analyzed by gas chromatography using a Trace GC gas chromatograph (Thermo Finigan, USA) equipped with a silica capillary column (Quadrex, 30 M, bonded carbowax 0.25 mm I.D×0.25 μm film, No 007-CW-30-0.25F, USA) and flame ionization detector (FID). Helium was used as carrier gas. The column temperature was programmed at 100°C from 200°C (5°C/min) and at 220°C from 240°C (3°C/min), and injector and detector were maintained at 200°C and 250°C, respectively.

At the end of the second feeding trial, chemical analyses of fish liver were performed by the standard procedure of AOAC (1995) for moisture, crude protein and crude ash. Crude lipid was determined using the Soxtec system 1046 (Tecator AB, Sweden) after freeze-drying the samples for 12 h. Blood samples were taken from the caudal vessels of five fish from each group by using a heparinized syringe after fish were starved for 1, 12 and 24 h and anesthetized with AQUI-S. Blood plasma were obtained after blood centrifugation (3,500×g, 5 min, 4°C) and stored at −80°C until glucose, insulin, GOT (glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase), GPT (glutamic pyruvic transaminase), TP (total protein), ALB (albumin), TG (triglyceride) and TCHO (total cholesterol) were analyzed. Plasma insulin was measured by a solid phase 125I radioimmunoassay (RIA) kit (Coat-A-Count Insulin®, DPC, USA). The assays were performed as described in the manufacture protocol. Standard solutions, samples and 125I tracer were added to duplicate antibody-coated assay tubes. Tubes were incubated at 20 to 24°C (room temperature) for 18 to 24 h. Tubes were decanted and radioactivity remaining bound to the tubes was quantified using a gamma counter (1470 Wizard, PerkinElmer Ltd, Finland). Concentrations of insulin in samples were calculated from logit-log representation of the standard curves (Stimmelmary et al., 2002). The plasma glucose, GOT, GPT, TP, TG and TCHO were measured using a blood chemical analyzer (DRI-CHEM 3500 I, Fujifilm Ltd. Japan) with commercial clinical investigation kit (Fuji DRI-CHEM slide, Fuji photo flim co. Ltd., Japan).

Statistical analysis

Data of Exp. 1 (amino acid and fatty acid compositions) and Exp. 2 (crude protein, crude lipid and crude ash) were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and significant differences among treatment means were compared using Duncan’s multiple range test (Duncan, 1955). Significance was tested at 5% level and all statistical analyses were carried out using the SPSS Version 10 (SPSS, Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical analysis among individuals having single value without replicate within group, such as Exp. 1 (PCV and Hb) and Exp. 2 (Glucose, Insulin, GOT, GPT, ALB, TP, TCHO, TG and HSI) were evaluated by the Wilcoxon test and Friedman test (Zimmerman and Zumbo, 1993). Statistical significance of the differences was determined by a significant level of 5% (p<0.05).

RESULTS

Whole body amino acid composition

The amino acid composition of the whole body is shown in Table 1. Total amino acid content of the initial group was higher than that of the other final groups (p<0.05). Difference in levels of total amino acid among initial and final groups was observed in three amino acids, glycine, lysine and arginine. Whole body amino acid composition between GE and control groups were not different (p>0.05).

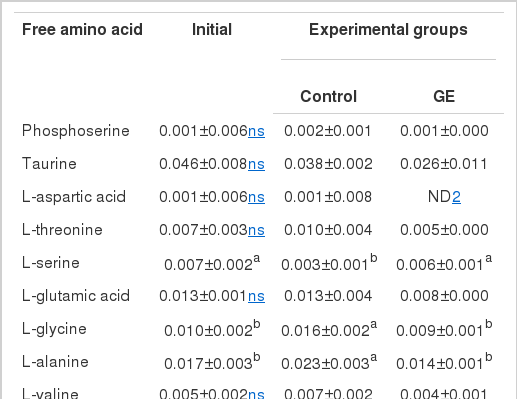

Whole body free amino acid composition

Levels of free amino acid in whole body are shown in Table 2. GE group showed lower levels of free amino acids than control group (p<0.05). However, individual free amino acid levels among three groups are not different (p>0.05) except for six free amino acids, L-serine, L-glycine, L-alanine, β-alanine, L-lysine and L-histidine (p<0.05).

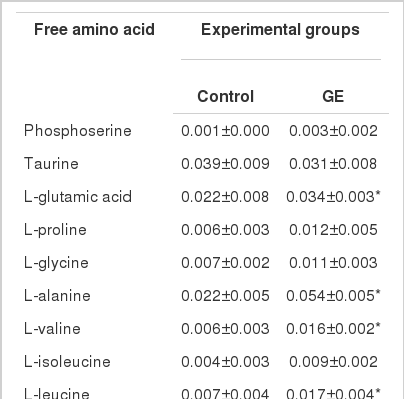

Muscle free amino acid composition

The free amino acid composition in muscle of juvenile sterlet sturgeon fed diets with or without GE is shown in Table 3. Major free amino acids in muscle of two fish groups were ornithine, histidine, alanine and taurine. Muscle contained significantly higher (p<0.05) glutamic acid, alanine, valine, leucine and phenylalanine for fish fed GE than for those fed control. Total free amino acid level in muscle was 0.267 to 0.337 mg/100 mg for control and GE groups, respectively, which was found to be significantly different (p<0.05).

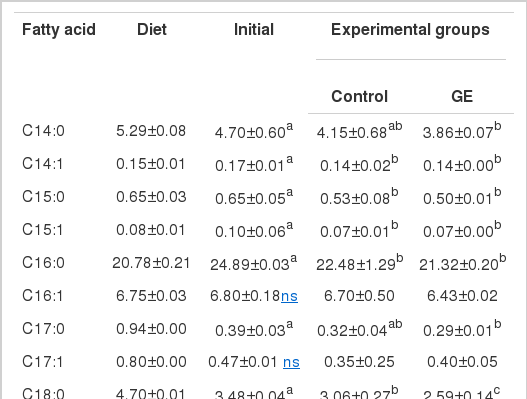

Whole body fatty acid composition

The fatty acid profile of the experimental diet and whole body of initial and final sturgeon fed the experimental diets for 5 wks is shown in Table 4. In both initial and final fish, 18:1n9, 16:0 and 18:2n6 were observed to be dominant fatty acids, of which 18:1n9 and 16:0 showed a significant decrease (p<0.05) from 30.1% for initial to 29.3% and 26.8% and from 24.9% for initial to 22.5% and 21.3% for control and GE, respectively. However, a slight increase in 18:2n6 from 12.4% for initial to 13.4% and 14.0% was found for control and GE, respectively. Final fish showed more prominent increase (p<0.05) in 20:5n3 and 22:6n3 compared to initial. The former was increased from 2.1% for initial to 3.3% and 4.2% and the latter from 5.2% for initial to 7.3% and 10.2% for control and GE, respectively. Similar trend was observed in 18:2n6 and 18:3n3 which were significantly increased from 12.4% for initial to 13.4% and 14.0% and from 0.1% for initial to 1.3% and 1.5% for control and GE, respectively. As a whole, lower saturated fatty acids (SFA) and monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) and higher polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) were found in GE than in initial and control, suggesting that dietary GE could stimulate the accumulation of 20:5n3 and 22:6n3 in fish body.

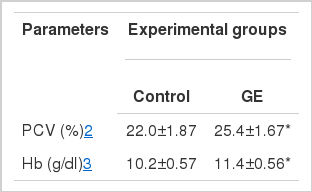

Hematocrit and hemoglobin analysis

Hematological characteristics of juvenile sterlet sturgeon fed diets with or without GE for 5 wks are given in Table 5. Mean values for PCV (hematocrit) and Hb (hemoglobin) were significantly different (p<0.05) between control (PCV, 22.0%; Hb 10.2 g/dl) and GE groups (PCV, 25.4%; Hb 11.4 g/dl).

Postprandial glycaemic response and blood plasma change

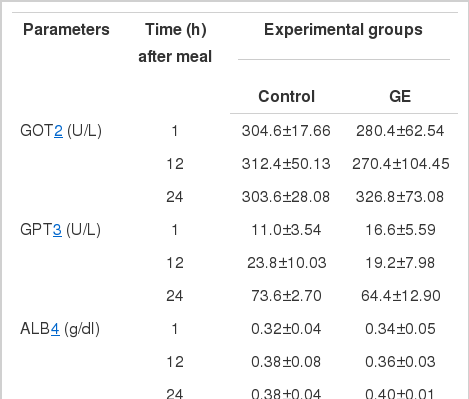

Plasma glucose and insulin concentrations of sterlet sturgeon fed diets with or without GE are shown in Table 6. Glucose level (mg/dl) of control fish 1 and 12 h after meal increased from 62.4 to 74.6 and it remained constant at 73.6 24 h after meal. However, the value 24 h after meal of GE group sharply decreased to 57.6, while similar change from 50.8 to 73.0 was observed 1 and 12 h after meal. Significant difference (p<0.05) in glucose level 1 and 24 h after meal was observed between two groups and the value in 12 h was significantly higher (p<0.05) than those in 1 and 24 h in GE group. On the other hand, insulin level (μIU/ml) of control in 1 and 12 h decreased from 5.06 to 2.72 and remained constant at 2.96 in 24 h. In contrast, the value of GE decreased from 10.56 to 2.60 and highly increased to 32.56 in each interval of time. Significant difference (p<0.05) in the value 24 h after meal was observed between two groups. However, there was no significant difference (p>0.05) between the values in 1 h and 12 h in GE group. The serological characteristics of juvenile sterlet sturgeon fed the experimental diets are shown in Table 7. Glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT) ranged from 304 to 312 U/L for control and from 270 to 327 U/L for GE. Glutamic pyruvic transaminase (GPT) ranged from 11 to 74 U/L for control and from 17 to 64 U/L for GE. Albumin (ALB) level after meal was relatively constant at 0.32 to 0.38 g/dl and at 0.34 to 0.40 g/dl for control and GE, respectively. Total protein (TP) level increased from 1.26 to 1.70 g/dl for control and from 1.54 to 1.94 g/dl for GE. Total cholesterol (TCHO) level 1 h after meal was significantly higher (p<0.05) in GE (48.4 mg/dl) than in control (28.8 mg/dl), since that time, the values were not greatly different both in 12 (36.4 vs 37.4 mg/dl) and 24 h (41.6 vs 50.0 mg/dl). Triglyceride (TG) level after meal increased from 578 to 678 mg/dl for control and from 638 to 816 mg/dl for GE. It was found that the value in 24 h was significantly different (p<0.05) between two groups.

Liver composition

Liver proximate composition of initial and final sturgeon fed diets with or without GE for 23 days is shown in Table 8. Liver weight increased from 1.87 g for initial to 2.76 g for control. The highest HSI (2.85%) was found in control, while it was not significantly different (p>0.05) between initial (2.43%) and GE (2.37%) group. Liver moisture significantly decreased (p<0.05) in two experimental groups, compared to that (63.6%) of initial. Similar trend was shown in protein level, which was decreased from 10.9% for initial to 7.9% for control. In contrast, lipid significantly increased from 22.5% for initial to 30.0% for GE. Fish fed control had 27.2% lipid in their liver, which was significantly lower (p<0.05) than that of 0.5% GE. Ash level did not show any significant difference (p>0.05) among initial, control and GE, ranging from 0.89% to 0.99%.

DISCUSSION

Garlic contains a variety of organosulfur compounds such as allicin, ajoene, S-allylcysteine, diallyl disulfide, S-methylcysteine sulfoxide and S-allylcysteine (Chi et al., 1982). A wide array of beneficial effects of garlic such as antihypertensive, antihyperlipidemic, antimicrobial, hypoglycaemic, antidote (for heavy metal poisoning), anticarcinogenic, hepatoprotective and immunomodulation have been reported by several researchers (Foushee et al., 1982; Macmahon and Vargus, 1993; Agarwal, 1996; Augusti, 1996; Bordia et al., 1996; Yeh and Liu, 2001). Allyl sulfides in garlic enhance glutathione S-transferase enzyme system and garlic also has immune enhancing activities that include promotion of lymphocyte synthesis, cytokine release, phagocytosis and natural killer cell activity (Kyo et al., 1998). Studies on garlic as an alternative of growth promoter in livestock production were conducted and its beneficial effects on growth, digestibility and carcass traits have been reported (Bampids et al., 2005; Tatara et al., 2008). There is a lot of anecdotal evidences about the use and effectiveness of garlic for fish. Much of these are positive, but there are also negative anecdotal reviews of the use of garlic. In livestock, a few research suggested that garlic did not affect growth performance (Horton et al., 1991; Freitas et al., 2001; Bampidis et al., 2005) because the pungent smell may lead to lower diet palatability.

Insulin is derived from a larger single chain precursor protein, proinsulin (Steiner and Oyer, 1967) which contains 81 amino acids and three disulfide bonds. Insulin itself consists of an A-chain usually of 21 amino acids and a B-chain usually of 30 amino acid residues connected by two disulfide bonds. In Russian sturgeon, the amino acid sequence of sturgeon insulin (A-chain; 21-amino-acid peptide, H-Gly-Ile-Val-Glu-Gln-Cys-Cys-His-Ser-Pro-Cys-Ser-Leu-Tyr-Asp-Leu-Glu-Asn-Tyr-Cys-Asn-OH and B-chain; 31-amino-acid peptide, H-Ala-Ala-Asn-Gln-His-Leu-Cys-Gly-Ser-His-Leu-Val-Glu-Ala-Leu-Tyr-Leu-Val-Cys-Gly-Glu-Arg-Gly-Phe-Phe-Tyr-Thr-Pro-Asn-Lys-Val-OH) is more similar to the amino acid sequence of mammalian insulins than of other fish insulins (Rusakov et al., 1998). The homeostatic role of insulin in mammals was succinctly summarized by Tashima and Cahill (1968). After feeding, insulin facilitates glucose uptake and incorporation into glycogen or conversion into lipid and stimulates amino acid incorporation into protein. In addition, insulin promotes incorporation of dietary lipid into adipose tissue and regulates plasma concentrations of glucose, amino acids and free fatty acids during fasting. The present study showed that the hypoglycaemic effect for juvenile sterlet sturgeon fed diet with 0.5% GE was accompanied with blood plasma glucose depletion and elevated blood plasma insulin (after 1 h and 24 h of meal). These results are similar to those reported in rats (Chang and Johnson, 1980; Augusti and Sheela, 1996; Preuss et al., 2001), where there is an association between garlic administration and the rise in circulating insulin. Jain et al. (1973) reported that garlic juice improved hyperglycaemia as compared with an insulin-secretagogue drug (tolbutamide) on studying glucose tolerance in rabbits. In various mammal species, the hypoglycemic and antidiabetic effect of garlic has been found (Chang and Johnson, 1980; Sheela and Augusti, 1992; Augusti, 1996; Kasuga et al., 1999) and can suppress the rise in hyperglycaemia and hyperlipidaemia in diabetic animals. The administration of the insulin secretagogue drug chlorpropamide in fish leads to the hypoglycaemic effects (Al-Salahy, 2003) and insulin injections into fish also induced hypoglycaemia (Ottolenghi et al., 1982; Carneiro and Amaral, 1983; Al-Salahy et al., 1994). These findings are similar to those resulting from garlic treatment (Al-Salahy and Mahmoud, 2003). Thus, our research suggested that garlic in diet for juvenile sterlet sturgeon (60 to 100 g) has positive effect on hypoglycaemia.

Fish and all animals need a constant source of amino acids for tissue protein synthesis and for synthesis of other compounds associated with metabolism, including hormones, neurotransmitters, purines and metabolic enzymes (Harlver and Hardy, 2002). Fish body proteins cannot be stored in major quantities and are continuously renewed through degradation and synthesis, free amino acid pool changes in its composition (profile) and concentrations, depending on the tissue (Carter et al., 1993), frequency and time after feeding (Tantikitti and March, 1995) and temperature and food (Knapp and Wieser, 1981). Since there is a slower rate of protein turnover in muscle than in other organs (Fauconneau and Arnal, 1985), the influence of dietary treatments, especially dietary amino acid profiles, may be more responsive in other tissues than in muscle. It is well known that insulin exerts a profound influence on the metabolism of amino acids and protein (Lotspeich and Shelton, 1949). The evidence for the role of insulin in the regulation of protein synthesis in fish was provided by Jackim and LaRoche (1973) who showed that injection of bovine insulin 1 μg/fish into Fundulus heteroclitus weighing 1 to 1.5 g resulted in stimulation of [14C] leucine incorporation from 45.6% in controls to 73.4% 18 h after injection. In a study on the European silver eel, Anguilla anguilla, Ince and Thorpe (1974) reported that 2 IU/kg cod insulin lowered blood glucose, amino acid nitrogen and cholesterol while bovine insulin at the same dosage lowered amino acid nitrogen only. Insulin was also implicated in the rapid clearance of an intraarterial load of amino acids. A study on the Japanese eel, Anguilla japonica, has shown that insulin at 5 IU/kg reduces the plasma concentration of all amino acids except citrulline (Inui et al., 1975). In the present study, whole body amino acid composition between both groups of fish was not different (Table 1). However, the levels of total whole body free amino acids decreased in GE group (Table 2), while total free amino acid level in muscle of GE group was higher than that of control group (Table 3). Our previous research suggested dietary garlic for juvenile sterlet sturgeon (60 to 100 g) could positively affect growth performance and N retention (Lee et al., 2012). The body amino acid pool is in a continuous state of flux in order to keep the pool relatively constant and amino acids are discretely released for synthetic purposes, oxidation for energy release, or conversion to fat. The promotion in insulin of GE group may induce acceleration for blood FAA uptake into muscle to strength growth performance.

Dietary lipids are important nutrients affecting energy production in most of fish and essential for growth and development. But, fish are known to utilize protein preferentially to lipid or carbohydrate as an energy source. Lipids are stored in several tissues and at high levels in sturgeon. Sturgeon may have muscle lipid content as high as or higher than that of other fish that are considered fatty, such as salmon and mackerel (Krzynowek and Murphy, 1987). Sturgeon fed high lipid diets preferentially deposits lipid in the liver and the digestive tract rather than in muscle (Decker et al., 1991). In present study, lipid in liver composition (Table 8) of juvenile sterlet sturgeon was greatly increased from 22.5% for initial to 27.2% and 30.0% for control and GE groups, respectively. Dietary GE might result in excessive lipid aggregation in liver because increase in protein utilization by fish fed GE diet could reduce role of lipid as an energy source for growth.

In this study, we were particularly interested in the levels of (n-3) PUFA [DHA, 20:5(n-3) and EPA, 22:6(n-3)] in whole body. It has been shown that (n-3) PUFA have several beneficial effects on human health (Simopoulos, 1989) and, in general, wild fish are considered to be the richest source of dietary (n-3) PUFA. It was reported that farm-raised fish have a lower level of (n-3) PUFA than their wild counterparts (Pigott, 1989). Greene and Selivonchick (1987) suggested that different species of fish have varying abilities to desaturate and elongate fatty acids. Rainbow trout have a relatively high ability to desaturate and elongate fatty acids, whereas some marine fish have a poor ability to do so. Xu et al. (1993) reported that white sturgeon has the ability to desaturate and elongate 18:2(n-6) and 18:3(n-3), so they could utilize the different lipids equally well. In the past, research has been focused to reduce fat, cholesterol, and SFA contents of poultry meat by dietary supplementation of garlic (Konjufca et al., 1997). Ao et al. (2010) reported that in fatty acids composition of egg yolk in laying hens, 3.0% fermented garlic powder supplementation resulted in a higher PUFA:SFA ratio compared with other treatments (control, 1%, 2% fermented garlic powder supplementation). Our present finding also accords with these results that juvenile sterlet sturgeon fed diet with GE have lower SFA and MUFA with higher PUFA than initial and control fish, suggesting that dietary GE could increase the accumulation of 20:5n3 and 22:6n3 in fish body. However, no comparisons with other studies could be made because investigations on the use of GE in relation to any sturgeon meat quality have not yet been reported.

In Table 5, it is shown that the hematocrit and hemoglobin level were higher in fish fed GE than in fish fed control diet. Shau et al. (2007) reported that the haemoglobin content was significantly (p<0.05) higher in the GE group (10 g garlic kg−1 feed) after 20 d. Leucocytes and erythrocytes play a non-specific or innate immunity and their count can be considered as an indicator of the health status of fish (Harikrishnan et al., 2003). The erythrocyte count increased with the administration of garlic, which might indicate an immunostimulant effect (Sahu, 2004). Attention has been focused on the changes in GOT and GPT activities which promote gluconeogenesis from amino acid, as well as on the changes in aminotransferase activities in the liver (Rashatuar and Ilyas, 1983; Abd-El-Hamid et al., 2002). In recent years, although some studies reported that the enzyme activities in serum of animals decreased significantly when they were fed diet containing garlic (Salah El-Deen and Rogers, 1993; Augusti and Sheela, 1996; EL-Shatter et al., 1997), our result did not show any significant difference in both GOT and GPT activities in blood plasma of both GE and control groups. Al-Salahy (2002) did not found a positive effect of garlic administration (5 h and 5 d) on serum TP and ALB to fish, Clarias lazera. Similarly, the present results did not showed any significant difference on TP and ALB level between GE and control groups. However, Metwally (2009) showed that total protein in serum was significantly high with fish fed diet containing any source of garlic (natural garlic, garlic powder, garlic oil). Although Yeh and Yeh (1994) revealed that sulfur compounds of garlic decreased the plasma concentration of cholesterol in rat resulting possibly from an inhibition of hepatic cholesterol synthesis. In our study dietary GE did not affect cholesterol level in the different hours except 1 h after meal. Reduction of triglycerides in blood serum of O. niloticus fed diets containing different forms of garlic was reported by Metwally (2009). However, Al-Salahy (2002) reported that the triglyceride level did not change, as well, level of serum total lipid remained same in the garlic administrated (5 d) group. Our results obtained no significant difference between GE and control groups in TG except 24 h after meal. Considering the data obtained herein and the above discussion, it was concluded that the supplementation of GE could influence amino acids levels of whole body and muscle, N utilization, whole body fatty acid composition and blood plasma content in juvenile sterlet sturgeon. However, further research is needed to validate the present results.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Gyeonggi Province Freshwater Fisheries Research Institute for donating the fish and providing the facility.