Conservation of indigenous cattle genetic resources in Southern Africa’s smallholder areas: turning threats into opportunities — A review

Article information

Abstract

The current review focuses on characterization and conservation efforts vital for the development of breeding programmes for indigenous beef cattle genetic resources in Southern Africa. Indigenous African cattle breeds were identified and characterized using information from refereed journals, conference papers and research reports. Results of this current review reviewed that smallholder beef cattle production in Southern Africa is extensive and dominated by indigenous beef cattle strains adaptable to the local environment. The breeds include Nguni, Mashona, Tuli, Malawi Zebu, Bovino de Tete, Angoni, Landim, Barotse, Twsana and Ankole. These breeds have important functions ranging from provision of food and income to socio-economic, cultural and ecological roles. They also have adaptive traits ranging from drought tolerant, resistance to ticks and tick borne diseases, heat tolerance and resistance to trypanosomosis. Stakeholders in the conservation of beef cattle were also identified and they included farmers, national government, research institutes and universities as well as breeding companies and societies in Southern Africa. Research efforts made to evaluate threats and opportunities of indigenous beef cattle production systems, assess the contribution of indigenous cattle to household food security and income, genetically and phenotypically characterize and conserve indigenous breeds, and develop breeding programs for smallholder beef production are highlighted. Although smallholder beef cattle production in the smallholder farming systems contributes substantially to household food security and income, their productivity is hindered by several constraints that include high prevalence of diseases and parasites, limited feed availability and poor marketing. The majority of the African cattle populations remain largely uncharacterized although most of the indigenous cattle breeds have been identified.

INTRODUCTION

The global livestock sector is characterized by a growing dichotomy between livestock kept extensively by a large number of smallholders and pastoralists (600 million) in support of food security and livelihoods, and those kept in intensive commercial production systems [1,2]. In Southern Africa, over 90% of animal keepers are classified as smallholders and 75% of the farm animals which largely consists of indigenous breeds belong to the smallholder sector [3]. For example, indigenous cattle breeds such as Nguni, Mashona, Tswana, and Tuli are critical components of smallholder beef production in Southern Africa. Currently southern African region is richly endowed with many indigenous beef cattle breeds such as the Afrikaner, Tuli, Tswane, Barotse, Boran, Mashona, Nkone, Angoni, and Nguni/Landim (Mozambique), but is threatened by increased uncontrolled crossbreeding with exotic genotypes like the Hereford, Santa Getrudis, Aberdeen Angus and Simmental [4]. For example, in the case of the emerging sector of South Africa non-descript/crossbred cattle make up 66.4% of herds [5]. Although the purpose of crossbreeding in beef cattle is partly to combine breed differences and partly to make use of heterosis to improve production, it has threatened the exisistence of the indigenous cattle genotypes in Southern Africa [6,5]. These indigenous breeds among others are not well characterized or described, and are seldom subject to structured breeding programmes to improve performance. More importantly, these indigenous animal genetic resources are in a continual state of decline due to indiscriminate crossbreeding and institutional policies that support use of high producing exotic breeds in the smallholder areas [7]. The erosion of indigenous cattle genetic resources is currently a cause for concern in Southern Africa as they are an integral contributor of food, agricultural power, agrarian culture and heritage, and genetic biodiversity in the region [8,5]. Overall, animal genetic diversity enables farmers to select stocks or develop new breeds in response to changing conditions, including climate change, new or resurgent disease threats, new knowledge of human nutritional requirements, and changing market conditions or changing societal needs [2].

Southern Africa’s climate and production environment vary widely and include numerous harsh environments that combine high temperatures, droughts and floods and epidemic of disease and parasites related to climate change [3]. These conditions give the indigenous breeds a competitive edge over exotic breeds that have been raised in temperate climates. Given the current harsh production circumstances and potential for significant future changes in production conditions and production goals, it is crucial that the value provided by indigenous cattle genetic diversity is secured through characterisation, conservation and development of breeding programmes. It is important to note that development of strategies for characterisation and conservation of indigenous cattle requires consideration of multiple factors including biology of animals, agroecology of the environment, production system of the animals, purpose of rearing and affordability of the owners duly to be addressed [9]. Thus, characterization and conservation of indigenous cattle breeds, including their unique products, should be accorded high priority in the Southern African region. That is essential in designing conservation programmes for indigenous cattle and could strengthen the future position of the indigenous cattle breeds in the expected new smallholder cattle production systems and changing production environments. To design successful conservation programmes for indigenous cattle breeds, it is essential for the stakeholders to prepare strategic long-term plans to accommodate the challenges of limited resources such as land, feed, labour and capital. The current review provides an overview of efforts made to characterize, conserve and develop breeding programmes for indigenous beef cattle genetic resources in Southern Africa and discusses threats and opportunities for the development of breeding and conservation programmes in the smallholder areas.

Distribution and status of indigenous beef cattle breeds in Southern African smallholder areas

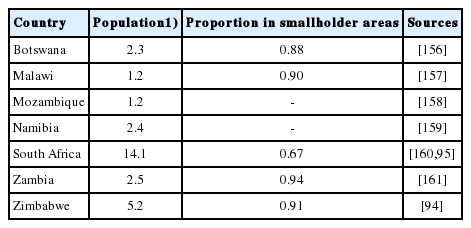

Currently, about 180 breeds of cattle have been recognized in sub-Saharan Africa [10,11]. The number includes 150 breeds of indigenous cattle of which 25% are found in Southern Africa. The distribution of the indigenous beef cattle in sub-Saharan Africa is shown in Figure 1. Rewe et al [12] reported that Sanga cattle (Bos taurus Africanus) breeds such as Nguni, Tuli, Barotse, Tswana, Tonga, and Mashona are the dominant indigenous beef cattle breeds found in Southern Africa. Phenotypically humped, zebu cattle (Bos indicus) breeds such as Malawi Zebu and Angoni are also common [13]. Of these breeds, 65% to 90% of the cattle are found in smallholder areas (Table 1). The genetic distinctiveness between these cattle breeds, however, remain largely unknown. In that regard, it may be more appropriate to talk about African cattle populations or ecotypes instead of breeds. A breed is a homogenous group of livestock which are phenotypically unique from other groups or subpopulations of the same species [9,15].

Overall, the purity of indigenous cattle breeds is under threat due to crossbreeding and institutional polices that support the use of imported breeds [14,10,8] Pure Nguni cattle numbers in South Africa for example, declined from 1,800,000 in 1992 to 9,462 in 2003 [7]. The situation is aggrevated by lack of records and uncontrolled mating systems practiced in the smallholder areas [10], which, in most cases, promote inbreeding. In addition, both planned and indiscriminate crossbreeding between indigenous and imported breeds generated non-descript/crossbred cattle, which are now dominant in most Southern African smallholder areas [16,17]. For example, in the case of the emerging sector of South Africa non-descript/crossbred cattle constitute about two-thirds of the cattle population in this sector [14]. Although, African cattle genetic diversity remains large, cattle populations or breeds continue to face extinction. According to [10], 22% of African cattle breeds have already become extinct in the last century and 32% of indigenous African cattle breeds are in danger of extinction [12]. Moreover, some breeds that are critically endangered have fewer than 1,000 animals, including South African sanga breeds such as the Nkone, Pedi, and Shangan [143]. According to [13], extensive crossbreeding, replacement with exotic breeds, and social and environmental disasters have placed these indigenous bovines at risk of extinction.

Extension messages in the colonial era created the perception that, for beef production, indigenous cattle breeds are inferior to imported breeds because of their small-frame [12]. To compensate for the perceived lower beef production potential of indigenous cattle, crossbreeding of these cattle with exotic breeds, was commonly practiced, with minimal within breed selection program for the indigenous breeds [13]. The end result was a continuous erosion and loss of indigenous cattle diversity. It is, therefore, important to comprehend the role of indigenous cattle in the smallholder areas and characterize them to objectively inform their utilization and conservation before they disappear [18].

The economic value of indigenous beef cattle in smallholder areas

Studies by [19] and [8] revealed that smallholder farmers keep beef cattle for multiple purposes. Rural households depend on cattle for meat and milk as sources of food and income through sales and for by-products such as horns and hides [19]. The hides are further processed to make carpets, seat covers, harnessing ropes, drumbeats and hats for the spirit mediums [20,21]. Cattle also provide dung for manure, floor polish/seal and fuel [16], either in the form of dried dung cakes or via the production of biogas. In addition, cattle are a source of draught power for cultivation of crops and transport of goods in smallholder areas [22,9]. Cattle are an inflation-free form of banking for resource-poor people and can be sold to meet family financial needs such as school fees, medical bills, village taxes and household expenses [23,24]. They are a source of employment, collateral and insurance against natural calamities. More importantly, indigenous cattle are valuable reservoirs of genes for adaptive and economic traits, providing diversified genetic pool, which can help in meeting future challenges resulting from changes in production sources and market requirements [8–25].

Socio-cultural functions of indigenous cattle

Socio-cultural functions of cattle include their use as bride price (lobola) and to settle disputes (as fine) in smallholder areas [26,19]. Cattle are reserved for special ceremonial gatherings such as marriage feasts, weddings, funerals, circumcision and ancestral communion (e.g bira- an all-night ritual, performed to call on ancestral spirits for guidance and intercession) [8,9]. Cattle are given as gifts to visitors and relatives, and as starting capital for youth and newly married man [21]. They are used to strengthen relationships with in-laws and to maintain family contacts by entrusting them to other family members [23]. Cattle play an important role in installation of spirit mediums, exorcism of evil spirits and are given as sacrificial offerings to appease avenging spirits [9,16]. Some farmers keep cattle for prestige and pleasure [22]. The relative importance of each of the cattle functions vary with farmers’ objectives, production system, rangeland type, region and socio-economic factors such as gender, marital status, age, education and religion of the keepers [26,24,16]. Efforts to characterise, conserve and develop breeding programs should, therefore, emphasize the understanding of farmers’ objectives, and socio-demographic factors. From this knowledge, constraints and opportunities faced by resource poor smallholder cattle farmers can be identified and sustainable developmental strategies formulated [23].

Ecological values of indigenous cattle breeds

Livestock serves multiple purposes in supporting the ecological and biological wellbeing of our planet. For smallholder farmers in mixed crop–livestock production systems, securing a supply of manure can be among the most important reasons for keeping animals. For example, a study conducted by [27] in the Gambia, indicated that among mixed farmers with fewer than ten cattle, manure supply ranked as the second most important reason for keeping cows and third for keeping bulls. Among farmers with larger herds, manure supply was reported to be the most important livestock function. The significance of livestock manure in crop production is noted above. Manure plays a key role in crop production by providing essential crop nutrients [26–28]. However, dunging also affects the health of grassland soils. In grazing systems, the effects of dunging have to be considered along with the effects of grazing and trampling [29]. Outcomes depend on the particular characteristics of the ecosystem and on the type of grazing management practised. Soil health is fundamental not only to the productivity of grazing systems, but also to their roles in carbon sequestration and water cycling. Many rangelands have suffered soil compaction and erosion as a result of livestock grazing. However, appropriately managed grazing can also contribute to improving soil health [29,30]. In many countries, grazing livestock play a significant role in the creation and maintenance of fire breaks and hence in reducing the spread of wildfires [31,32]. They can also contribute to reducing the risk of avalanches [33].

Kugler and Broxham [34] reported that cattle play an important role in biodiversity conservation such as weed and fire control, maintenance of biodiversity and carbon sequestration. It is important that the use of livestock is properly managed and regularly monitored in order to make sure that both the cattle and the eco-system are healthy [34]. Livestock make their most important contribution to total food availability when they use feed sources that cannot directly be eaten by humans [35]. This occurs, for example, when livestock graze areas that cannot be used for crop production, when they eat crop residues such as straw and stovers, by-products of food processing and waste food products that are no longer edible to humans. These cases can be contrasted with those in which animals are fed on feeds that could otherwise be used directly by humans (e.g. grains). Food production clearly falls within the provisioning category of ecosystem service. However, in some cases, the removal of unwanted plant material also constitutes a service. In grazing systems, the benefits concerned may relate to the removal of plant material that creates a fire hazard or the control of invasive species. In mixed systems, livestock may be used to control weeds (e.g. on fallow land) or in the management of crop residues [36].

CHARACTERISATION AND THE ADAPTIVE TRAITS OF INDIGENOUS BEEF CATTLE BREEDS

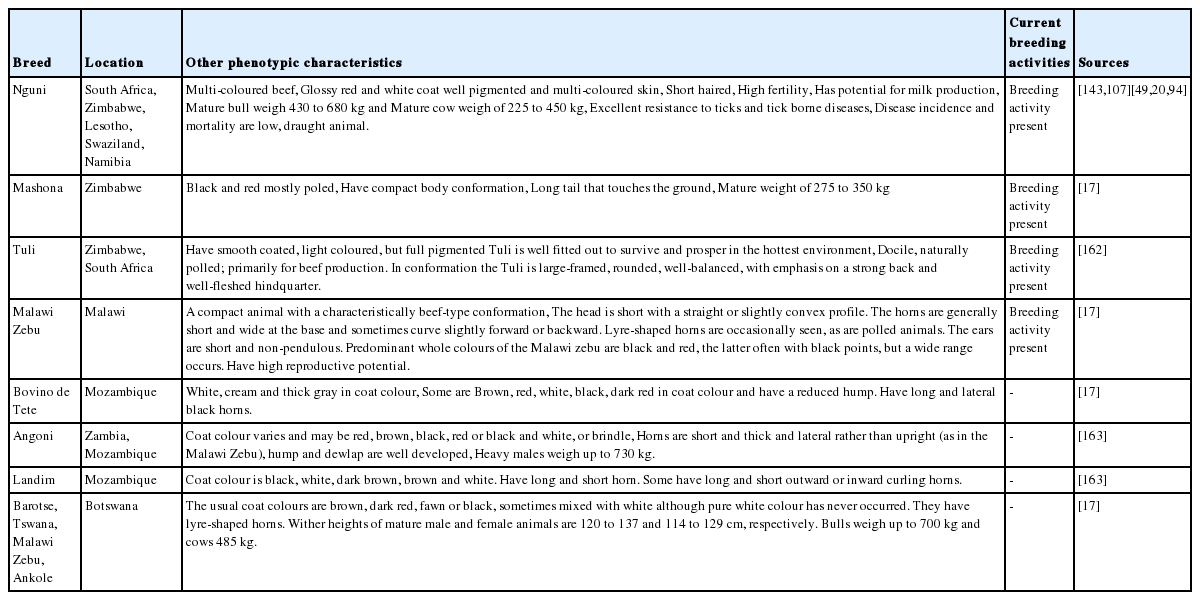

Indigenous cattle breeds in Southern Africa have unique morphological features which distinguishes them from other cattle (Table 2). These include horn shape and size (e.g. Ankole and Kuri cattle: [11,37,38] and coat colour (i.e Nguni) as shown in Figure 2. In addition to physical features, non-visible traits such as disease resistance, climatic stress resistance and productivity traits also differ among breeds. These characteristics are largely the result of natural and human selection [38].

Morphological features of indigenous cattle. A, Multi coloured Skin from Nguni cattle; B, Multi coloured Nguni cow and calf; C, Elongated horns of Ankole cattle.

Adaptability traits of indigenous beef cattle

Adaptability of an animal can be defined as the ability to survive and reproduce within a defined environment or the degree to which an organism, population or species can become or remain adapted to a wide range of environments by physiological or genetic means [39]. The level of production achieved by a particular genotype in harsh environments depends on the contribution and expression of many different traits which may be partitioned into those directly involved with production such as feed intake, digestive and metabolic efficiency, measured in the absence of environmental stress and those involved with adaptation such as low maintenance requirements, heat resistance, parasite and disease resistance [40].

Drought tolerant

According to [41] indigenous beef cattle have an advantage for their natural attributes of better feed utilization in case of poor forage conditions, or hardiness and survival in extreme climate changes. High daily temperatures and soils in the arid regions influence the type, quality and quantity of forages available for livestock [42]. For example, the Nguni, a major indigenous cattle breed in Southern Africa, is small to medium sized breed and adapts well to the harsh environments of South Africa’s smallholder areas where droughts are periodic and dry season nutrition [43,44]. To cope with drought and forage seasonality, Nguni cattle have low nutrient requirements for maintenance, and excellent walking ability, which enables it to walk long distances in search of grazing and water [45,46]. Nguni also has good selective grazing and browsing abilities, which enables it to obtain optimal nutrition from the available natural vegetation, thus enabling it to survive under conditions that bulk grazers such as the European cattle breeds would find extremely testing [47;48]. Although it is small to medium sized, has meat quality characteristics that compare favourably with European beef breeds [47,49]. The smaller size of the indigenous breeds with lower growth rates and milk production levels and high reproductive performance have also been considered as adaptation to the availability of low quantity and quality forages [43,50,51]. The amount of nutrients required to maintain an animal to undertake day to day physiological processes necessary for survival (such as tissue building and repair) depends among others on body size [43,52]. The small size of the indigenous breeds is, therefore, a result of natural synchronization of the genotype with available feed resources. In these marginal production areas where feed resources are limiting, both in quantity and quality, the large sized breeds are more likely to suffer reproductive impairments than the smaller breeds.

Resistance to ticks

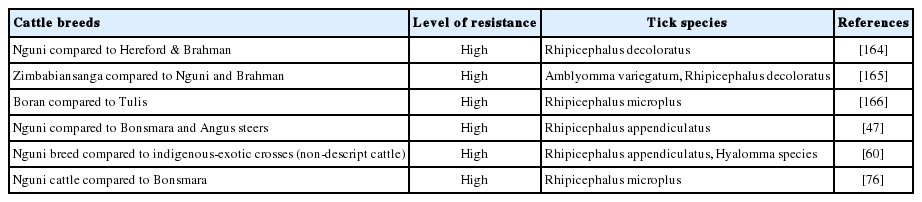

Tick infestation is one of the major problems that farmers face [53], causing economics losses in the cattle industry [54,55]. Africa loses $160 million in tick and tick-borne diseases’ (TBD) related to cattle deaths annually [56,57]. African Bos indicus cattle are believed to be more resistant to infestation by cattle ticks compared to taurine animals [58]. Several studies have been conducted to determine the resistance of Nguni cattle to ticks under both controlled [59,49] and uncontrolled conditions [60–62]. Under both conditions the Nguni breed had lower tick loads than exotic breeds and non-descript crossbreds. The beef cattle breeds and their level of resistance to specific tick species are shown below (Table 3).

Mwai et al [63] revealed that, the Tswana cattle from Botswana are also resistant to heavy tick challenges. These findings concur with [11] who also studied the same breed. [4] reported that Mashona cattle were more resistant to ticks and had high calving and weaning rate under marginal environmental conditions characterising most smallholder areas when compared to some exotic breeds. The resistance to ticks in sanga breed has been attributed to coat characteristics such as colour, hair length and density [48], grooming behaviour and delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity reaction to tick infestation [65]. An understanding of the mechanisms behind genetic resistance to ticks and TBD in livestock species could improve breeding programmes to develop animals that are more resistant and productive [62]. Genetic variation in resistance of livestock should be quantified within and across breeds so that appropriate strategies are adopted in breeding programmes. The host and tick genomics and their proteomics, such as gene expression profiles, are likely to facilitate studies addressing the sequencing, annotation, and functional analysis of their entire genomes [62]. This could provide valuable information for improving tick control.

Resistance to tick borne diseases

Besides causing blood loss and decreased milk or meat production, ticks transmit a number of diseases, including babesiosis, anaplasmosis, and cowdriosis. The Nguni cattle of Southern Africa have been reported to be resistant to tickborne diseases [60]. Marufu et al [60] showed that, Nguni cattle had lower seroprevalence for Anaplasma marginale and Babesia bigemina in the cool-dry and hot-wet seasons. The seroprevalence of TBD was lower in the Nguni breed [60]. Indigenous cattle have been known to have natural resistance to TBD [67]. As a result, they perform better under harsh environmental conditions and in as much as ticks may affect them the damage will be minimal as compared to European breeds.

Resistance to nematodes

Parasite infections are one of the greatest causes of diseases and loss of productivity in livestock with most grazing livestock being at risk from infection by gastrointestinal (GI) nematode parasites [68]. Besides TBD, internal parasites, GI nematodes in particular, are among the important factors limiting cattle productivity in Southern Africa. Grazing ruminants are always exposed to GI, which reduce feed intake, feed conversion efficiency, growth performance [69,70,71], draught power performance and cow fertility [72], can result in loss of blood and even death [73]. These parasites are a significant impediment to the efficient raising of cattle on rangelands [74]. Only the presence of worms and deaths in cattle are noticed by resource-poor farmers and viewed as the most important economic losses [73]. The greatest economic losses associated with nematode parasitic infections however, are subclinical [69] and these go unnoticed in cattle on rangelands. For the objective assessment of economic losses caused by GI nematodes in cattle on communal rangelands, there is a need to identify common nematodes and determine their load and prevalence. Information on nematodes loads and prevalence conducted under both uncontrolled and controlled on-station conditions is limited. Ndlovu et al [52] compared three breeds across seasons on sweet rangeland in South Africa and found that indigenous Nguni cattle had the lowest faecal egg counts compared to Bonsmara and Angus. [75] and [76] revealed that, Nguni versus non-descript crossbred cattle had the lowest egg loads and worm burdens. Further research to determine the resilience of the Nguni breed to internal parasites, especially GI could be important.

Resistance to trypanosomosis

Tsetse-transmitted trypanosomosis continues to be a serious and costly disease to cattle, despite multifaceted attempts to control it [77]. Although trypanocidal drugs can be useful, parasite resistance to these drugs increases yearly. Fortunately, locally adapted beef cattle breeds such as Nguni, Tuli, Tswana, and Mashona found in areas of high tsetsefly challenge show consistent tolerance to these infections [78]. Various studies have been undertaken since 2007 to elucidate the biological basis for trypanotolerance [79,80,78]. Two physiological mechanisms seem to be involved: i) increased control of parasitaemia; and ii) greater ability to limit anaemia [77]. Overall, mechanisms of disease and parasite resistance, resilience or tolerance of indigenous beef cattle and the probable development of immunity merit investigation [81].

Heat tolerance

Exceptional challenges faced by livestock in arid and semi-arid environments are numerous, but heat stress is one of the major challenges that animals have to deal with for a longer period of the year [82]. Heat stress in beef cattle on veld/savannah is expected to increase as a result of changing weather patterns on a global and regional scale [83,84]. High ambient temperatures outside the thermo-neutral zone cause significant changes in physiological processes including feed intake, due mostly to the direct effects of thermal stress. Nardone et al [85] revealed that, hot environment impairs production (growth, meat, and milk yield and quality) and reproductive performance, metabolic and health status, and immune response. Gregory et al [86] revealed that, heat could affect meat quality in two ways. First, there are direct effects on organ and muscle metabolism during heat exposure which can persist after slaughter. Second, changes in cattle management practices in response to temperature changes could indirectly lead to changes in meat quality. For example, changing to heat-tolerant Bos indicus cattle sire lines could lead to tougher beef. Owing to their adaptation to local environments, it is important to find ways of conserving indigenous cattle breeds in Southern Africa.

METHODS OF CONSERVING INDIGENOUS BEEF CATTLE BREEDS

There are two major conservation methods; in situ and ex situ conservation, which are interlinked [15]. The ex situ method involves conservation of animals in a situation removed from their habitat. It is the storage of genetic resources not yet required by the farmer and it includes cryogenic preservation. The in situ method is the conservation of live animals within their production system, in the area where the breed developed its characteristics [87,88]. It can also be referred to as on-farm conservation. Such conservation consists of entire agro-ecosystems including immediately useful species of crops, forages, agroforestry species, and other animal species that form part of the system [89]. Under the in situ conditions, breeds continue to develop and adapt to changing environmental pressures, enabling research to determine their genetic uniqueness.

According to the World Watch List for Domestic Animal Diversity prepared by the [90], the requirements for effective management for conservation needs at the country level for each species include identifying and listing the breeds. Therefore, this conservation provides opportunities for utilisation, breed evolution and development, maintenance of production and agro-ecosystems and ecological development. There is consensus that in situ conservation is the method of choice for the smallholder farmers [91]. The Convention on Biological Diversity, FAO and various workers [92] also emphasized the importance of strong in situ programmes supported by ex situ complementary measures. The costs can be borne by the farmers themselves, governments or commercial entities that may develop niche market products from the genotypes [93]. In situ conservation has the main disadvantage that the forces that currently threaten genetic resources remain [92]. Given that most local breeds have small effective populations the risks of inbreeding and genetic drift are always high. In addition, small populations tend to be more vulnerable to unforeseen disasters [8]. One of the biggest problems inq Southern Africa is lack of resources to develop in situ conservation programmes.

In Southern Africa, most countries for example South Africa, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Malawi are well-endowed with structural capacity to effectively run in situ and ex situ breed conservation strategies. An establishment of a unity of purpose is vital for the success of the programme in these countries [94]. These countries have many institutions both government research centres, parastatals, universities, colleges and breed societies which can spearhead the conservation of animal genetic resources for smallholder beef cattle farmers. These institutions could also be mandated to take charge of the indigenous cattle breeds by employing in situ conservation and cryo-preservation with utilisation. A minimum effective population size of 250 animals per breed per institution would be ideal to minimise inbreeding and maximise the contribution of each individual to the next generation [92,95]. The technical know how, infrastructural development and land sizes can accommodate at least one breed per institution. Funding through subsidies based on the difference between the potential production of the conserved strain and that of the alternative replacement breed or its crosses could be important. Parastatal institutions in Southern African countries may offer crucial support for the smallholder areas to implement in situ conservation of smallholder beef cattle genetic resources. Selection on characteristics traditionally valued (adaptability, low plane of nutrition, disease resistance, cow productivity, and growth performance) could be done with the help from these institutions organised at local level. Concerted efforts of private corporate (Breed Societies, farmer unions, non-governmental organisations) and government parastatals would provide long-term funding, personnel, capital to mobilise stock and implement a well-planned breeding programme. Farmer-based projects can be funded nationally and be coordinated through central programmes. The projects can be effective and conserved breeds continue to adapt and evolve within sustainable changes in local agricultural practice, climatic and environmental conditions of Southern African countries. It is therefore important for different stakeholders to participate in the conservation of beef cattle breeds in Southern African smallholder farming communities.

STAKEHOLDERS IN CONSERVATION OF BEEF CATTLE BREEDS

Farmers

Farmers are the custodians of farm Animal Genetic Resources (AnGRs) [15]. They come in different hues from commercial to subsistence smallholder farmers. Each has an interest in the current and future AnGR and is usually called upon for in situ conservation efforts. For successful conservation programmes, farmers need information on the value of the smallholder beef cattle genetic resources, training on beef cattle production, access to markets and other services, recognition of their rights, economic and legal incentives and legislative support for benefits sharing [64,96,97]. In addition, current carcass classification systems tend to disfavour the smallholder beef cattle as compared to the exotic breeds kept in commercial farms [98].

A study by [94] showed that, almost all indigenous cattle in the smallholder sector are not performance recorded because of the numerous functions they perform. Although this national pool of indigenous cattle breeds has been diluted by introduction of exotic genotypes, there remain some areas where relatively pure stocks can still be found [99,100].

National government

There are several stakeholders involved in or who should benefit from conserving AnGR [101]. One of the key stakeholders is the national government as the custodian of legislation, national policy and also as an active participant of conservation; and as a signatory to most conventions that aim to conserve AnGR (e.g. Convention on Biological Diversity). Issues of sovereignty, rights and fair trade can only be addressed at the government level [89]. There are examples worldwide where governments have taken a lead role in conserving AnGR [102,103,15], and Southern African governments can do the same. It seems only the South African government, is the only country in Southern Africa with a conservation programme in place for local pigs. This initiative can be successfully harnessed to conserve indigenous beef cattle breeds from a country grouping perspective by incorporating other Southern African countries.

In 1998 the Department of Rural Development and Agrarian Reform (DRDAR) in South Africa came up with a Bull Scheme in the smallholder and small-scale commercial sector of the rural communities [104,105]. The project distributed high performing Nguni bulls to control inbreeding in the smallholder areas. This facilitated effective community management institutions to develop cattle production and marketing opportunities for Nguni cattle in rural areas [105]. This programme initially introduced 35 Nguni bulls into five communities in the Northern Province and six communities in the Eastern Cape [106,105]. These communities had organized farmer groups that were willing to participate in a development scheme and to contribute a minimal amount towards the maintenance of the bulls. At the end of three years, the community returns the bull, which will then be placed in another community. Farmers were not encouraged to remove or castrate existing exotic breeds in their area but merely to upgrade the community animals to Nguni breed [107]. By the year 2008, about 150 registered Nguni bulls were distributed across the rural communities of the Eastern Cape Province. The Bull Scheme was considered slow in effecting change in the communities. This was because of the presence of other bulls of several breeds/genotypes. There was no recording of animal performance and record keeping. This also meant that conservation efforts of the Nguni breed did not have much impact. Despite these weaknesses, the Bull Scheme is still operational [108] and is important for the conservation of smallholder beef cattle genetic resources. Therefore for effective conservation, there is need for accurate records when measuring animal performance for example bulls through performance testing. The government is also recommended to build infrastructure for smallholder beef cattle.

Research institutes and universities

Technological adjustments and the increasing consideration of target group involvement in livestock breeding programmes may offer better possibilities for raising production by breeding in low-input and medium-input livestock breeds. In that regard, research institutes should contribute to the research, documentation, inventory and characterisation of AnGR [15]. For example, the University of Fort Hare (UFH) Honeydale farm maintains a large population of indigenous Nguni cattle which has been the subject of various studies (Table 4). Research institutes in Zimbabwe rear some indigenous beef cattle for example the Mashona cattle at Henderson and Makoholi and Nguni cattle at Matopos Research stations. The Mara research station in South Africa keeps Bonsmara herd of cattle whilst the Chitedze research in Malawi keeps the Malawi Zebu. However, these efforts are not well coordinated and should be more focused for them to have an impact on the conservation of local beef cattle breeds. Ex situ conservation of beef cattle genetic resources can be done on farms of research institutes and universities with the assistance of the government. The Nguni cattle of South Africa are a model example of the ex situ in vivo conservation of an indigenous breed: they were conserved on government farms as well as university farms (e.g University of Fort Hare) and, once their numbers had been increased by breeding, they were made available for commercial production.

Initiatives by the University of Fort Hare and other development agencies

The UFH was instrumental in initiating the community-based conservation of Nguni cattle in South Africa [105,21,95] as a follow-up of the Bull Scheme. By engaging the Development Bank of Southern Africa, Industrial Development Cooperation, ECDRDAR, and private donor, Adam Fleming, the Nguni Cattle Programme became widespread in the Eastern Cape Province [109,105,95,110,98]. The programme became visible in the EC province uplifting the livelihoods of cattle farmers in smallholder and small-scale commercial areas and maintenance of genetic material of the Nguni breed [95,98]. Interested communities were offered two registered bulls and 10 in-calf heifers to allow them to build up a smallholder open-nucleus herd. All the existing bulls in the community were replaced by registered Nguni bulls. After five years, the community enterprise would give back to the project two bulls and 10 heifers, which are then passed on to another community [105,19]. The ‘pay it forward’ system was used where each community pays dividends of its original gift to another. Some of the conditions of the project were; communities should have fenced grazing areas and practicing rotational resting at specified stocking rates [105].

The beneficiaries of the Nguni Cattle Programme were either a rural farming community/village or emerging/small-scale farmers in LRAD farms [98]. The programme aimed at empowering rural farmers with livestock farming skills and developing their entrepreneurship abilities. This was after the realisation that cattle ownership is fundamental to social status and self-esteem of the rural farmers [110]. The long-term goal of the programme was to develop a niche market for Nguni beef and skins and to position the smallholder and small-scale farmers for the global beef market through organic production and product processing [19]. The Nguni Cattle Programme has so far benefited 72 communities in the Eastern Cape Province out of the target of 100 as at July 2012 [95,98]. The participatory approach of the programme provides a sustainable mechanism of establishing dispersed nucleus of Nguni herds in the rural areas. The Nguni Cattle Programme has a development committee, made up of interested stakeholders, in charge of the development of infrastructure, training of farmers, and the redistribution of animals. The implementation of the model is conducted in collaboration with the ECDRDAR [105,111]. The determination of breeding objectives with farmer participation for this in situ conservation is considered important for the sustainability of the programme. The active participation of the Industrial Development Cooperation IDC saw the involvement of five other provinces after 2006 targeting emerging black farmers and rural farming communities using the same criteria. The provinces include Limpopo, North West, Northern Cape, Free State, and Mpumalanga. The size of the nucleus herd was increased to one bull to 25 to 30 in-calf heifers [112]. Official data on the success of the initiatives is scanty with reports of seventeen beneficiaries in Mpumalanga Province, six in Northern Province and four in North West. In the KwaZulu Natal (KZN) Province, conservation activities are promoted by the KZN Nguni cattle club which is a non-profit organization. The KZN Nguni cattle club strives to conserve and enhance the unique characteristics of the Nguni cattle breed, and promote the proliferation of the Nguni population in the province [113]. Therefore, the Nguni cattle improvement programmes are recommended to supply a complete package of back up services such as genetic resources, performance recording schemes, genetic evaluation, rangeland management aids and appropriate infrastructural support to the benefiting communities. There is need for effective and continuous monitoring and evaluation of these projects, especially in the implementation phases to detect and rectify unfavourable developments on time.

Breeding companies and societies

Breeding companies tend to conserve genetic diversity within and between their inbred lines and they also tend to have patent protection for their genetic resources [102]. Breeding societies like the Nguni, Tuli, and Mashona cattle breeders societies are also involved in breeding and conservation of beef cattle genetic resources. However, they are also interested in the future value of AnGR diversity because they are the ones that are most affected financially by any deleterious change in production environment. The consumer is the main driver of changes in the market and is also the source of money for conservation efforts [114,15]. The value of the consumer might not be very significant in relation to conservation of smallholder beef cattle genetic resources as ‘most of the benefits produced by local livestock in marginal production systems are captured by producers, rather than consumers’ [114]. However, a close integration between the consumer and the producer in the value chain has produced benefits elsewhere and would be of use in Southern Africa). Breeding programmes are, therefore, suggested for Southern Africa within the concept of regional genetic improvement programmes controlled by breed societies, breeding companies, government and national agricultural research systems.

POTENTIAL COST IMPLICATIONS OF CONSERVATION

Every sound conservation effort bears a cost which differs with perspective on the particular population or breed, countries, regions and production environments [114,91]. Although the conservation potential is considered as a good indicator for conservation decisions, it does not give information on how to allocate the conservation budget to maximize the conserved diversity [91]. It is necessary to assign appropriate shares of the conservation budget to the different breeds once the decision is made as to which population or breeds should be sampled. Several methods of estimating the likely cost of conservation efforts has been described elsewhere [115,92,116]. Firstly, the costs and effects for the different conservation schemes in terms of reduced extinction probability need to be established and known. The costs can typically be subdivided into variable costs, which depend on the number of beef cattle cryo-conserved sample and the fixed costs, which are necessary to establish the conservation scheme inter alia.

THREATS AND OPPORTUNITIES TO CONSERVATION OF INDIGENOUS CATTLE BREEDS

Low cattle productivity

Cattle feed shortages, high incidences of diseases and parasitism, poor breeding practices and poor marketing management are the major threats to beef cattle production [117,16,118]. These threats limit smallholder beef production and hence the need to characterize and conserve indigenous beef cattle genetic resources for sustainability of smallholder beef farmers in Southern Africa.

Quality and availability of animal feed

Extensive grazing is the common practice by the resource-poor farmers where animals entirely rely on communal natural pasture [119,98,118]. Seasonal deficiency in feed quality and quantity particularly during the second half of the dry season is the major constraint to smallholder livestock production [16,120]. Poor management of natural pastures, inappropriate grazing management, and natural pasture fires also limit the availability of fodder in the smallholder areas [121]. Natural pasture quality and quantity is highly variable in the tropics with crude protein dropping below 5% in the dry season [122,123]. In the sour natural pastures (sourveld), the highest crude protein values are recorded during the wet season. The reduction in protein content of grasses and the increase in lignin content during winter reduce the overall digestibility of the grasses [124]. Information on the effect of seasonal changes on feed dynamics and management in smallholder areas is scarce, making it difficult to assess the efficiency of utilisation of smallholder natural pastures by beef cattle [106]. In a study by [125,126], it was revealed that crossbreds had higher body weights than Nguni cattle. Sweet rangeland had lower cattle weights than the sour rangeland. Body weights for both breeds were higher on the sweet rangeland in the hot-wet and post-rainy seasons compared to other seasons. The observed breed differences in ALP values in the hot-dry and hot-wet seasons reflect differences in growth, body size and weight for the cattle in this study. Small framed animals, have low feed intake and, consequently, lower skeletal growth [127] than local crossbreds. Therefore the opportunities for using indigenous beef cattle breeds are that they are drought resistant and they survive in the natural pastures sometimes under limited forage and hence they need to be conserved.

Prevalence of diseases and parasites

In Southern Africa, diseases are a major constraint to livestock production [48,61,62]. Animal health issues are barriers to trade in livestock and their products, whilst specific diseases decrease production and increase morbidity and mortality [16,48]. These diseases include anthrax, foot and mouth disease, black-leg and contagious abortion. The outbreaks of such diseases in Southern Africa can be a threat to the smallholder cattle producers who do not have medicine and proper disease control infrastructure [61,62]. Furthermore, movement of cattle and their by-products are difficult to monitor in the smallholder areas. The effects of endo- and ecto-parasites are mainly high mortalities, dry season weight loss which reduce fertility through nutrition induced stress [48]. This has negative financial implications in controlling the effects of diseases [128] and productivity implications as 70% of calves are born during the dry season [129]. Studies by [130] and [120] cited smallholder herd mortality rate as high as 18%, with disease accounting for 60% of herd mortality for smallholder cattle in Masvingo district [131]. The most common diseases reported by farmers are cowdriosis and babesiosis [120, 131]. The situation is worsened by the unavailability and high cost of drugs [132] and inadequate veterinary officials [16]. A survey by [133] has shown that most of the farmers raising cattle are rarely visited by veterinary officials serve for contact with the dip attendants during dipping days.

The farmers rarely use drugs to treat their animals as they have limited access to veterinary care in terms of support services, information about the prevention and treatment of livestock diseases, and preventive and therapeutic veterinary medicines [60]. The concerned farmers rely on the use of traditional medicines to combat the constraint of nematodes, ticks and tick borne diseases [117,133,95]. The epidemiology, burdens and susceptibility to parasites and diseases in different classes and strains of livestock require research [134,118]. Parasites with huge impacts on growth and mortality, such as tapeworm, should be prioritised in the research efforts [135]. Affordable ways of controlling parasites, such as the use of ethno-veterinary medicines should also be evaluated to complement the conventional control methods [136] as they can provide low-cost health care for simple animal health issues [137]. It is therefore important to conserve and use local adapted beef cattle breeds which are resistant to local diseases and parasites.

Poor marketing management

Livestock marketing, in most smallholder areas, is poor and characterised by absent or ill-functioning markets [138]. A baseline study by the International Crop Research Institute in Semi Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) revealed lack of organised marketing of beef cattle in Zimbabwe smallholder areas [130]. Smallholder farmers resort to the informal way of marketing their cattle where pricing is based on an arbitrary scale, with reference to visual assessment of the animal. Middlemen are the main buyers and purchase live animals from farmers for resale at cattle auction points and to abattoirs in towns often benefiting more than the farmers themselves [131]. Apart from selling to local butcheries, farmers do not have ready markets where they can take their animals to if they need to sell their animals therefore usually end up under-pricing their animals in cases of emergencies [130]. Generally, smallholder cattle production in South Africa has been associated with a low off-take rate of 2% to 5% and hence there is need for marketing of the indigenous beef cattle so that more priority is given on their conservation which will improve on their pricing as well [139,140].

Poor breeding practices

Lack of controlled breeding in smallholder areas result in inbreeding, which then cause poor growth rates in cattle [133,141]. Recent studies in the rural communities of South Africa practicing low-input animal agriculture have highlighted the concern of cattle breeding practices [16,104], a high bulling rate, and a high number of young bulls, heifers and young cows [142,98]. Absence of animal selection was observed in communal and small-scale Nguni cattle enterprises practising community-based in-situ conservation [106,104]. The Nguni, an indigenous cattle breed in South Africa, found in rural areas have not undergone the intensive selection programs that are used for the exotic and commercially-oriented breeds [143]. This can be because of the uneasiness and rigorous nature of standard performance data collection to the majority of the less educated communal dwellers [144]. Cattle records for traits of economic importance are needed for accurate performance evaluation in terms of performance trends, selection criteria and mating system designs. It is therefore prudent to base animal selection on the high-value traits that a communal farmer understands, easily measure, and derive direct economic value. There are no structured breeding systems and appropriate infrastructure such as paddocks, therefore, cows and bulls of unknown genetic merit and bloodlines run together all year round [104]. In developing countries and low-input production systems such breeding schemes and structures are uncommon and livestock farmers have usually limited access to improved breeding stock or artificial insemination services and rely mainly on their own traditional breeding practices [141]. Often improved genetic material with the desired characteristics for the particular production environment is not available [141].

Animal performance recording systems have been known for long to affect genetic improvement programs with negative results in the communal areas of most developing countries [145]. The absence of performance records, particularly of the indigenous breeds, can lead to undefined breeding seasons and random mating [104]. A considerable number of livestock breeding programs have been reported to have failed because of poor performance data recording and trait identification [146]. The consequences of uncontrolled mating are well documented and include, among others; production of un-uniform animals, presence of undesirable and genetic defects, and inbreeding depression [121,147]. Furthermore, the potential to alleviate poverty and improve food security through livestock development interventions in the smallholder sectors of most developing countries was hampered by lack of participation in the planning and designing of breeding programs by the community [145, 148,146].

Cattle ownership and gender roles

These socio-economic characteristics of the farming environment such as cattle ownership necessitate participatory determination of breeding objectives for in situ conservation [110,16]. Some level of input from the farmers could be important in sustaining the conservation initiatives in terms of objective assessment of animals, mating strategy and performance recording. Cattle ownership is strongly skewed, with a small number of people owning large herds and the majority owning few animals or none at all and stock numbers tend to be less evenly distributed in smallholder areas than in small-scale commercial areas [16, 106]. The smallholder farmers tend to have multiple owners of cattle within a herd and to some extent one animal have two or more owners [105,106]. Cattle ownership is mostly male-dominated with duties carried out by children and older age-groups that are mainly found in the rural areas [110,16]. Cattle ownership has been thought as a fundamental basis of social status and self-esteem to the rural farmer [110]. To identify constraints and opportunities for technological interventions into smallholder beef production, gender analysis should be carried out. This will assist in preventing frequent misdirecting of technologies and services to the wrong gender group. According to [149], gender analysis is a tool for understanding men and women’s roles and the responsibilities in various activities, their use of resources, access and control to resources and benefits, participation in decision-making and contribution to household income and food security [149,16,106]. The involvement in different types of agricultural work for men and women in most African communities depend mostly on social, cultural, local customs and religious influence [149 150].

Infrastructure and cattle handling facilities

Most of the infrastructure and cattle handling facilities and dip tanks in the smallholder areas in Southern Africa were built using funds from local or national governments and development agencies [150]. Cattle facilities make it easy to carry out the basic animal husbandry activities such as animal identification, castration, pregnancy diagnosis, animal treatment, vaccinations and live-weight measurements. For example, about 75% of rural livestock owners in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa use cattle handling facilities when treating their sick animals with herbal plants [168,95,98,] which need close contact with the animal. This investment is thought to enhance the husbandry activities thereby improving efficiency of the conservation initiatives.

Extension and services

The role of extension workers is to get information from the researcher and transmit it to the rural farmers [151]. In Zimbabwe for example, the extension farmer ratio is 1:250 in some smallholder farming areas. To fulfil this role effectively extension workers should keep abreast with new technological developments through strong linkages with researchers. Extension officers play a role in using the participatory appraisal techniques to identify cattle marketing problems and solutions [152]. Furthermore, this improves service delivery, thereby accelerating agricultural development [149,16,106]. The involvement of community members using a bottom-up approach can instil the sense of ownership and responsibility and enable them to maintain their infrastructure [151,95]. Extension officers can cooperate with smallholder people and aid them in managing the conservation initiatives and improving the productivity of animals. The conservation and monitoring process of the programme initiatives are therefore best achieved with competent extension personnel.

FURTHER RESEARCH

Overall, information about phenotypic and genotypic description, distribution, total and individual numbers of indigenous cattle breed in Southern Africa and their contribution to household food security and income, and adaptation to the changing local environment is lacking. Research effort should, therefore, be made to further characterize indigenous cattle breeds, generate accurate statistics on breed numbers and their contribution to household economy and food security. It should also focus on the adaptation of the indigenous cattle to the effects of climate change. It is also important to develop sustainable research programmes and projects that appropriately address the challenges that Southern African smallholder beef cattle producers face. Inadequate description, classification and evaluation of cattle have resulted in a poor understanding of the potential indigenous cattle breeds [4]. Breed differences can be established through molecular taxonomic characterisation, which can, in turn, serve as a guide on decisions relating to conservation [98,118] and improvement of these breeds [82]. Attributes of each breed will have to be identified and evaluated, to develop appropriate and sustainable breeding programmes. Microsatellites and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) can be used with ease in the studying of DNA sequence and variation [121,8,62] and result in enormous selection response. It could be important to conduct research in the smallholder areas, using modern technologies such as microsatellites to characterise cattle based on genetic diversity rather than region of origin since these animals may be genetically similar [8,62]. The rapid advances in genome sequencing and high-through put DNA techniques have led to new and more precise measures of genetic diversity and coancestry and inbreeding coefficients [62]. These new measures can be used in the genetic management of populations for increasing its effectiveness [153]. In South Africa, microsatellites have been used to evaluate the genetic diversity among indigenous cattle and identify different cattle strains [154,62]. Recently technological advances in molecular genetics have greatly improved our ability to use information on DNA polymorphisms to select livestock [154]. Genome-sequencing efforts have resulted in the availability of a reference genome sequence for most livestock species including cattle. This has also resulted in the discovery of many thousands, and even millions, of SNPs, which are single–base pair variations of individuals from the reference genome. These SNPs can be genotyped in a cost-effective way by modern SNP-chip genotyping technologies [154]. For most of the major livestock species including cattle, low-cost SNP arrays (“chips”) with approximately 50,000 genome-wide SNPs are available. For cattle, a 700,000-SNP chip can be used as well.

To effectively design sustainable genetic improvement programmes, correct matching of genotypes with the prevailing and projected socio-economic and cultural environments should be considered [155], breeding objectives should be clearly defined. Adaptive traits, such as resistance to diseases and parasites and their adaptation to extreme weather conditions [4] and for traits of economic importance such as calving interval, age at puberty, age at first calving [154] should be emphasized to improve smallholder cattle production. Programmes that encourage farmers to keep records should be developed since the records form the basis for genetic improvement. Regarding within-breed selection, realistic performance and pedigree recording, with active farmer participation should be adopted so that breeders can use the records to help select superior animals. Indigenous breeds should be prioritised in selection of individual cattle for smallholder herd improvement. For example, [155] reported 74% calving rate for Mashona cows almost 20% higher than that of Sussex (56%), indicating the importance of selecting cattle before using them as breeding animals at smallholder level.

CONCLUSION

Although smallholder beef cattle in Southern Africa are hardy, their productivity is hindered by several constraints that include high prevalence of diseases and parasites, limited feed availability and poor marketing. It is important to develop concerted, coordinated and comprehensive farmer training, research and development programmes to address these constraints for smallholder beef cattle producers. Conservation of Southern African beef cattle genetic resources could be imperative as these have been shown to be a useful integral part of agro ecosystems in some smallholder areas. The reasons for conserving smallholder beef cattle vary from current utility to the ability to meet future challenges in a dynamic environment. The options available include in situ, ex situ conservation techniques and their combination. There is a big policy gap in Southern Africa with regard to conservation of AnGR in general and it is imperative that policy makers be made aware of the value of AnGR. The costs of conservation can be met by increasing the market value of neglected breeds so that they eventually become self-sustaining. This requires the identification of the beef breeds, their characterization and development of marketable products from these breeds. The nations in Southern Africa have the potential to apply breed conservation strategies through securing long-term funding, revamping institutional activities, training technical personnel and co-ordination of management efforts. By so doing, this will promote conservation of smallholder beef cattle and enhance sustainable development to smallholder beef cattle farmers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation (NRF), Republic of South Africa. We thank Lizwell Mapfumo, Denice Chikwanda and Allen Chikwanda for constructive suggestions on the study and for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.