INTRODUCTION

Oxidative reactions serve as the fundamental part of numerous biochemical pathways and cell functions. For instance, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are not only by-products of normal oxygen metabolism in aerobic organisms, but acting as signaling molecules regulating physiological and biological process, therefore, redox-sensitive gene expression regulated by ROS has become increasingly appreciated [

1]. Once the levels of reactive species exceed the neutralizing ability of antioxidant system, such imbalance thereafter causes oxidative stress, leading to the activation of stress-sensitive intracellular signaling pathways, consequently cause damage to cellular macromolecules responsible for pathological conditions and diseases [

2].

Genetic selection toward fast growth rates in order to have lean and large breast muscles make domestic avian, especially broilers, are extremely susceptible to oxidative stress [

3]. Furthermore, free radical can be produced via endogenous metabolism and exogenous stimuli, suggest that these reactive species productions in the body is substantial, and a variety of biological molecules can be easily damaged once without proper protection [

4,

5]. Consequently, restricting oxidative processes is of prime importance for decent animal health, growth, production and economic feasibility.

Since nutrition is one of the most pertinent external factors in the prevention of diseases development, and the restricted ability of adaptive systems in animals to conquer oxidative stress, dietary supplementation with materials possessing antioxidant capacity become a decent candidate for external help in boosting endogenous defense mechanisms by influencing the redox sensitive molecules and thus identifying an important level of gene-nutrition interaction [

6]. Several studies have demonstrated that as being secondary messengers to influence gene expression, ROS signaling route could be affected directly or indirectly by molecules attending lipid metabolism [

7]. Moreover, oxidative stress induced by ROS accumulation is also considered to impair the optimal functioning of the immune system [

8], showing the importance to target molecules involved in these signal transduction network.

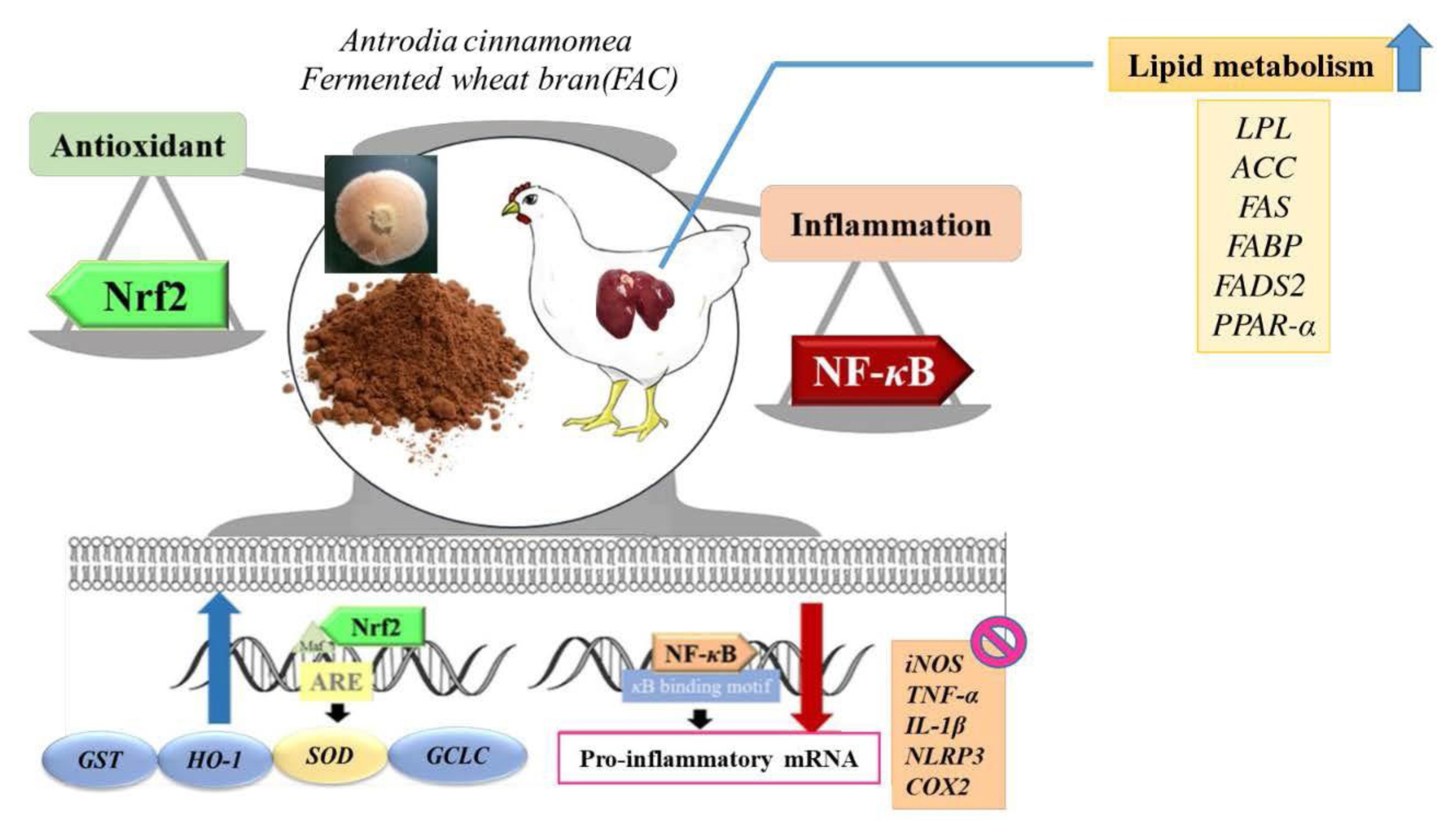

Since many components of the cell signaling network would converge on transcription factors, by tracing those upstream and downstream molecules, we could simply clarify the pathways involved in specific conditions. Based on the urgency to tackle the severity of oxidative stress in animal production, focusing on oxidative-related genes are of importance. Therefore, aiming at redox-sensitive transduction pathways such as nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2), nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) turns out to be a promising way.

Nrf2 is the principal transcription factor regarded as a mas ter regulator for the antioxidant response via translocating to bind to the antioxidant response element located in the promoter region of genes encoding numerous phase II detoxifying antioxidant enzymes and related stress-responsive proteins. These include glutathione S-transferase (GST), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), and glutamate cysteine ligase (GCL) that play key roles in cellular defense by enhancing the removal of cytotoxic electrophiles or ROS [

9]. In comparison with the mechanism of direct antioxidants, antioxidant actions driven by Nrf2 activation are regarded as indirect antioxidant regulation. Since indirect antioxidants act through gene expression, their physiological effects last longer than those being exerted by direct antioxidants. Inflammatory responses to a wide variety of stimuli mainly attribute to up-regulation of the proinflammatory transcription factor- NF-κB. Since it is a kind of redox-sensitive transcription factors, NF-κB responses to a number of stimuli including ROS [

10]. After activation, NF-κB would translocate to nucleus, and then induces the expression of different inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, enzymes such as cyclooxygenase (COX2) and nitric oxide synthase (NOS), and many other genes related to cellular transformation, invasion, metastasis and inflammation [

11]. Additionally, PPARs are transcription factors belonging to the nuclear receptor superfamily, among the three subtypes, PPARα activation is associated with a number of cellular process including lipid and lipoprotein metabolism, antioxidant defense, and anti-inflammatory response, being viewed as an attractive target regulated by nutrient [

8]. Considering the absence of Nrf2 is associated with increased oxidative stress, leading to amplification of cytokine production, as NF-κB is more readily activated in oxidative environments [

12], and that PPARα-mediated activation of lipid metabolism is capable of positively activating cellular protective Nrf2 pathways [

13] and repressing inflammatory genes through negatively interfering transcriptional activity of NF-κB [

14]; applying materials possessing the ability to affect these signaling pathways would be promising diet supplements in poultry husbandry for their long term effects and effectiveness.

In our separate manuscript, results demonstrated that di etary supplementation of fermented wheat bran by Antrodia cinnamomea (solid-state fermented wheat bran by Antrodia cinnamomea for 16 days, FAC) could improve the antioxidant capacity of chickens, better intestinal microflora and serum lipid profile. Moreover, due to the close related association among lipid metabolism, antioxidant and inflammatory response, the present study aims to study the effects of FAC on the components of signal transduction network in the above three parts, in order to elucidate the underlying regulatory control mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal management

Four hundred 1-d-old male broiler chickens (Ross 308) were evenly divided by weight (approximately 41±0.5 g/bird) and then randomly allocated to one of the five treatments. Each treatment group had four replicates per pen, with 20 birds per pen (totaling 80 birds per treatment). The temperature was maintained at 34°C±1°C until the birds reached 7 days of age; it was then gradually decreased to 26°C±1°C until the birds reached 21 day of age. After this point, the broilers were maintained at room temperature (RT, approximately 27°C). The experiment was conducted at the ranch of National Chung Hsing University, Taiwan, and the experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC NO:102-126). The birds in the control group received corn-soybean meal basal diet; the 5% WB group was fed the basal diet with 5% replacement of wheat bran (WB); the 10% WB group was fed the basal diet with 10% replacement of WB; the 5% FAC group was fed the basal diet with 5% replacement of solid-state fermented wheat bran by

Antrodia cinnamomea (AC), AC mycelia was kindly provided from Department of Forestry at National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan (Dr. Sheng-Yang Wang lab), for 16 days (FAC); and the 10% FAC group was fed the basal diet with 5% replacement of FAC (

Table 1). All birds received starter (1 to 21 days of age) and finisher (22 to 35 days of age) diets

ad libitum and had free access to water. The proximate composition of the diets was analyzed according to the AOAC [

14]. Crude protein, crude fat, ash, and acid detergent fiber levels were determined using methods 990.03 (Kjeldahl N×6.25), 945.16, 967.05, and 973.187, respectively; the results showed no major deviations from the calculated values. During the entire experimental period (35 days), the diets were formulated to meet the nutrients requirements suggested by Ross Broiler Management Manual [

15] and NRC [

16].

Sample collection

At 21 and 35 d, eight birds (two birds per replicate) were randomly selected from each treatment group for sampling. Blood samples were collected via wing-vein puncture into a tube containing 1% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). The samples were then centrifuged at 3,000×g for 10 min to obtain the serum, and the aliquots were transferred into microfuge tubes. Sera were kept on ice and protected from light to prevent any oxidation during sample collection. Samples were stored at −20°C until analysis. The birds were euthanized by electrical stunning for extermination, and then the abdominal cavities were opened for liver collection.

Liver RNA isolation and quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

The procedure for RNA isolation and purification were performed followed the manual of RNA isolation kit (AllBio Science, Inc., Taichung, Taiwan). In brief, after washed in ice-cold physiological saline, approximately 0.5 g of each tissue was incubated in the binding buffer provided in the kit, and ground with a pestle and mortar. Seventy-five μL protease supplied, and mix the solution thoroughly by vortexing. After incubate for 20 minutes at 56°C, equal volume of RNase-free 70% ethanol was added to the lysate. The solution was vortexed thoroughly to disperse the precipitate which may form after adding ethanol. Centrifuge briefly and add all the lysate into the spin columns, and then centrifuge again at 12,000×g for 30 seconds, then discard the flow through. Four hundred μL clean buffer was added to the spin column, do the centrifuge again at 12,000×g for 30 s, and then discard the flow through. Five hundred μL wash buffer was then added into the spin column, perform the centrifuge on the empty column at 12,000×g for 2 min at room temperature in order to remove ethanol residue and then air-dry the column matrix for 20 min. Place the spin column into a clean 1.5 mL RNase free tube. Add 50 μL of RNase-free water into the spin column matrix and incubate at room temperature for 1 min. After done the final centrifuge at 12,000×g for 2 min to elute RNA, the isolated RNA was stored at −80°C for the subsequent analysis.

RNA concentration was determined by spectrophotometry and diluted to 50 ng/μL. Total RNA concentration and purity, cDNA synthesis and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis (StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System. Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Rotkreuz, Switzerland) were determined as per the methods of Lin et al [

17]. Gene-specific primers were designed based on the genes of

Gallus gallus (chickens); and

Table 2 lists the features of the primer pairs. After the normalization of gene expression data, the means and standard deviation were calculated for samples from the same treatment groups.

Protein extraction and Western blot analysis

For Western blot analysis, nuclear and cytosolic extracts of the livers were prepared by Nuclear Extraction Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (FIVEphoton Biochemicals, San Diego, CA, USA). After quantification of protein concentration, equal amounts of proteins were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to poly-vinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (GE Healthcare Life Science, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Upon protein transfer, the blots were washed five times for 5 min in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and blocked with Blocking Buffer for 1 h prior to the application of the primary antibody. Chicken antibodies against NF-κB and Nrf2 were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). The primary antibody was diluted (1:1,000) in the same buffer containing 0.05% Tween-20. The PVDF membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody. The membrane was then washed five times with 0.05% PBST (PBS and Tween 20) for 5 min before being incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Specific binding was detected using hydrogen peroxide as substrates.

For the first animal trial, Protein loading was controlled using a monoclonal-mouse antibody against β-actin antibody (Biorbyt or b40714). For the second animal trial, cytosolic and nuclear protein loading was controlled using a monoclonal-rabbit antibody against glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase antibody (GeneTex, #GTX100118) and p84 (GeneTex, #GTX102919), respectively.

Band intensities of the proteins were quantified by densi tometric analysis using an image analysis system (Image J; National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Samples were analyzed in triplicate; a representative blot is shown in the respective figures.

Chicken peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolation

Whole blood of chicken was collected via wing-vein using a hypodermic syringe and inserted into tubes containing EDTA. The blood was gently layered on to Ficoll-Paque Plus and centrifuged at 200×g for 10 min. Chicken peripheral blood mononuclear cells (cPBMCs) were collected from the gradient interface; the plasma suspension was combined and washed three times with PBS and then centrifuged at 200×g for 10 min. After the suspension was removed, RPMI-1640 was used as the solvent for adjusting cell count to 108 cell/mL, which were pipetted 2 mL cell suspension into 6 well plates and cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 mixed with 95% air in an incubator for 2 h. After incubation, the cells were treated with 2,2′-Azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH, 10 mM) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 100 ng/mL) for 24 h. Pipetting the whole culture liquid into a sterilized tube, and centrifuged at 200×g for 10 min. One mL Trizol reagent was added and the mixture was stored at −80°C.

PrestoBlue assay for evaluating cell viability

The PrestoBlue agent is a highly sensitive and resazurin based reagent for assessing cell viability. The following procedures was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Isolated cPBMCs were seeded at a density of 1×107 cells/well in 96-well plates for 2 h. After incubation, the cells were treated with AAPH (10 mM) or LPS (100 ng/mL) for 24 h. After the treatment, the cells were washed by PBS. One hundred μL PrestoBlue solution was added to each well and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After the incubation, 100 μL of the PrestoBlue solution from each well was transferred to a new well in 96-well plate. The absorbance was recorded at 570 nm and 600 nm, and then counted the viability rate according to the manufacturer’s instruction, and the cell viability was expressed as a percentage relative to the cells untreated with plant compounds.

Measurement of nitric oxide content in chicken peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Nitric oxide (NO) production was indirectly assessed by measuring the nitrite levels in the culture media using Griess reagent assay. Briefly, isolated cPBMCs were seeded at a density of 1×107 cells/well in 96-well plates for 2 h. After incubation, the cells were treated with AAPH (10 mM) or LPS (100 ng/mL) for 24 h. The culture supernatant was harvested for nitrite assay. Each of 100 μL of culture media was mixed with an equal volume of Griess reagent (1% sulfanilamide, 0.1% naphthyl ethylenediamine dihydrochloride, and 5% phosphoric acid) and incubated at room temperature for 10 min, the absorbance was measured at 540 nm with a microplate reader.

Measurement of prostaglandin E2 content in chicken peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) level in cPBMCs was analyzed using kit purchased from Cayman Chemical Co., Ltd (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Briefly, isolated cPBMCs were seeded at a density of 1×107 cells/well in 96-well plates for 2 h. After incubation, cell culture supernatants were collected and assayed according to the manufacturer’s instruction. All samples were measured in triplicate. The total PGE2 in sample were expressed as pg per milliliter of culture supernatant.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by performing analysis of variances for completely randomized designs using the general linear model procedure of the SAS software program. Significant statistical differences among the various treatment group means were determined using Tukey’s honestly significant difference test. The effects of the experimental diets on response variables were considered to be significant at p<0.05.

DISCUSSION

Since the interaction of an organism with its nutrition sources is an intimate and complicated physiological event that is typically relying on multiple systems, even involves some minor microflora working in concert, targeting deeper and more original mechanisms become necessary. Thanks to the development of the field of molecular biology, researchers have been able to study the impact of diet on the animals at the clearer molecular level. By dissecting the mechanism of the effects of nutrients or the effects of a nutritional regime, this approach provide deeper insight into a more thorough process while changing diet for animals, it can also be used to evaluate the physiological effects of specific nutrients. The regulatory control mechanisms of these processes can be based on all levels from genetics and gene expression to the feedback of specific metabolites.

Recent research on AC has made great leap forward in re vealing its active components and their underlying molecular mechanism in cell lines or mammal model [

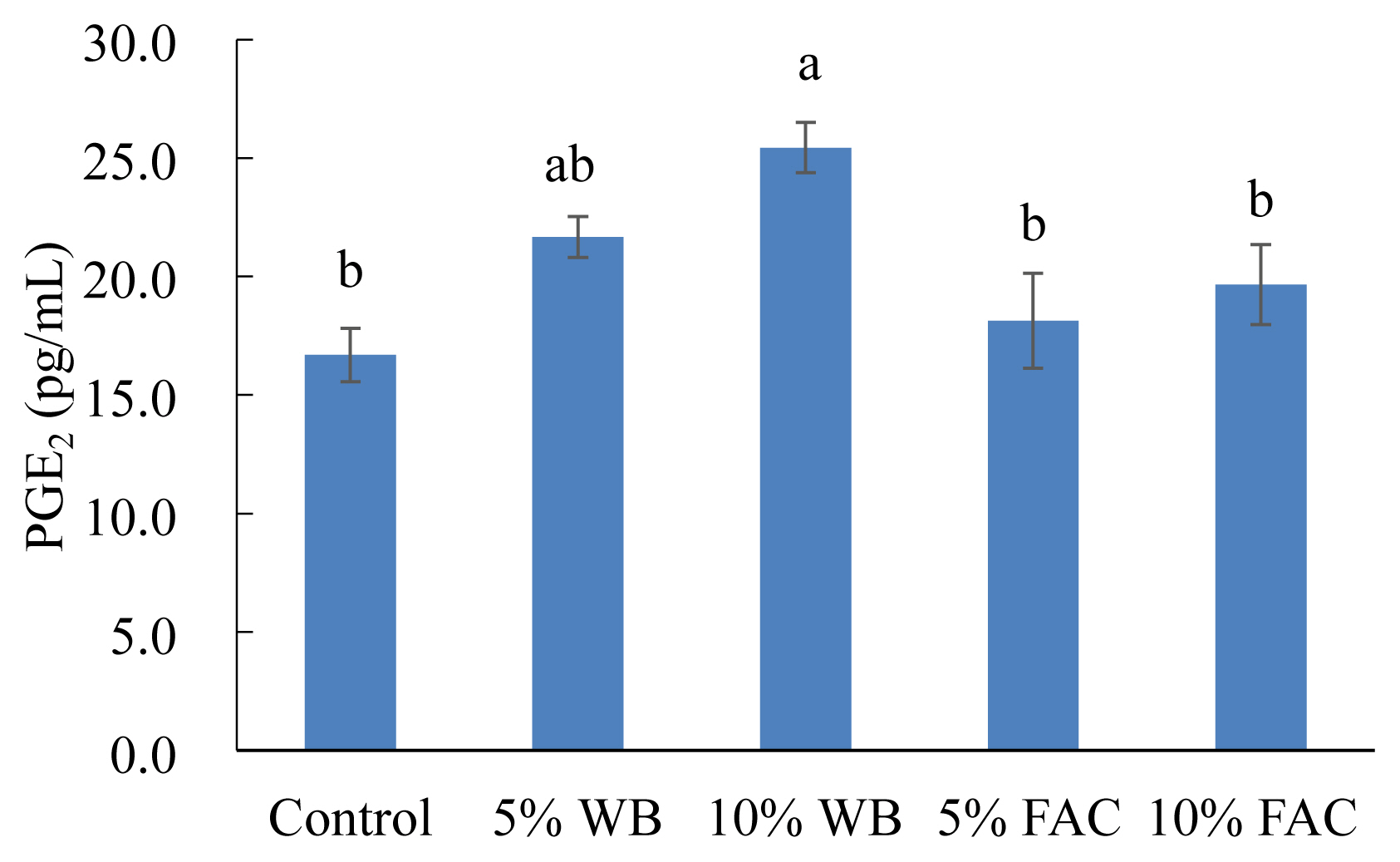

14] found that fermented culture broth of AC significantly inhibited LPS-induced NO and PGE

2 production and attenuated their corresponding genes, inducible nitric oxide synthase (

iNOS) and

COX2, by impeding NF-κB activation; at the same time, reduced production of cytokine in LPS-challenged group further supported the restricting NF-κB activity. Correspondingly, our results showed that chickens receiving diet containing non-fermented WB had relatively higher expression of NF-κB, iNOS, and COX2. High amount of non-starch polysaccharides (NSP) in WB are undesirable since NSP may induce gut inflammation in broiler chickens [

18], which may associate with NF-κB activation [

19]. Moreover, it’s noteworthy that

NLRP3 and

Caspase 1 genes expressed similar pattern in the same group. NLRP inflammasome is a multiprotein complex. NLRP3 is of importance lies on the fact that animals are not always exposed to pathogens; however, under the stimulants such as stress, damage associated molecular patterns would be released and activate inflammasome that induce maturation of pro-inflammatory cytokines. The subsequent cytokines, with those stimulated by NF-κB, would continuously activate NF-κB pathway, thus forming a positive auto-regulatory loop that can amplify the inflammatory response [

20]. Therefore, the increased level of NLRP3 and caspase 1 in two WB inclusion groups suggested that dietary supplementation of 5% to 10% WB may trigger stress response in broiler chickens, and thus activate NF-κB inflammatory pathway.

On the other hand, induction of Nrf2-regulated phase II antioxidant genes is considered as the core cellular defense in response to oxidative stress [

10]. These genes include GST and GCLC, both of which are indispensable molecules maintaining the homeostasis of GSH antioxidant system. Moreover, it’s noticeable that HO-1 was increased with significant level in the FAC groups as well. Previous literatures in mammal studies have proved the important role of HO-1 activation via Nrf2 pathway in countervailing inflammation [

21]. ROMO1 and NOX1 are regarded as positive regulators in intracellular ROS production [

22]. It has been proven that increased

ROMO1 expression, in response to external stress, enhances cellular ROS levels; its expression is also essential for cancer cell proliferation [

22]. NOX1 is one of the vital components of the enzymes catalyzing the production of O

2− and H

2O

2, both of which are members of ROS. Therefore, the amelioration of these two gene expressions in the current study were in line with the activation of Nrf2 and its downstream effects.

Currently, the antagonized role of Nrf2 pathway in NF-κB- modulated inflammation is gradually applied to animal science. For example, decreased SOD, catalase (CAT) and GSH-Px activities along with suppressed Nrf2 and augmented NF-κB expression in quails exposed to heat stress were improved by dietary supplementation with resveratrol and curcumin [

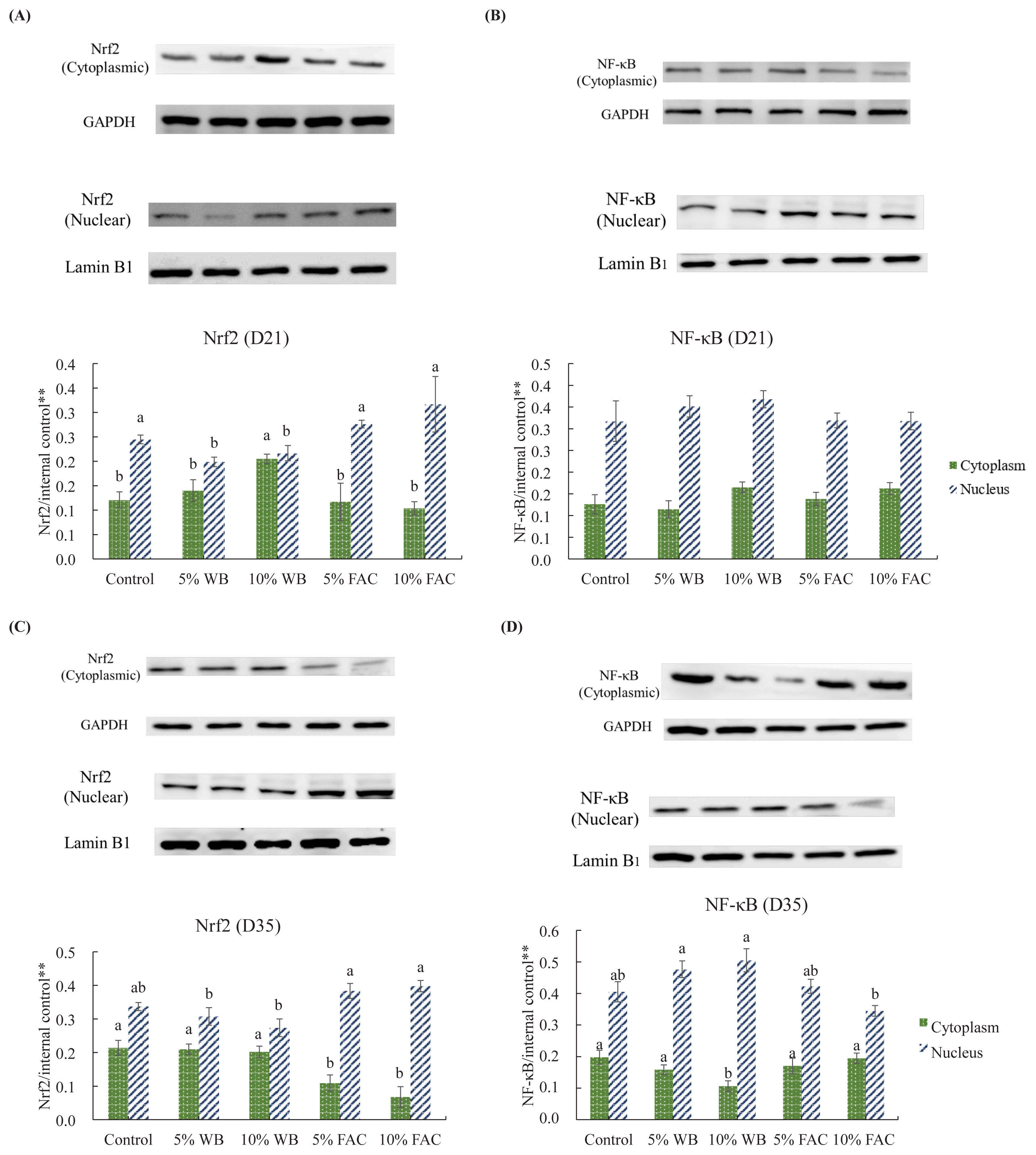

23], two phytochemicals well proved to have cytoprotective effects in medical research. In order to confirm the results of mRNA expression, Nrf2 and NF-κB protein level in the nucleus and cytoplasm of liver cell were analyzed. In unstimulated form, both transcription factors are generally sequestered by their suppressor in cytoplasm and be kept in low levels in nucleus. While activation, they would not be degraded by their oppressors, and they will thus translocate to the nucleus and to activate their downstream gene expression. According to our results, increased Nrf2 protein in the nucleus and the corresponding decrease in the cytoplasm suggested that in comparison with other three groups, 5% and 10% FAC supplementation drove the activation of Nrf2 protein. By contrast, NF-κB activation were inhibited especially in 10% FAC group in terms of relatively low level in the nucleus; and for chickens obtained diet containing non-fermented WB, relatively higher expression of cytoplasmic NF-κB and its downstream genes such as IL-6 and IL-1β suggested that chickens may be in a more stressful status, or even suffer from a certain level of inflammation.

In our study, the precursor and activator of

IL-1β,

NLRP3, and

caspase 1, were up-regulated especially in 10% WB group, implying more stressed condition of chickens. Previous literature has shown that activation of

IL-1β and

caspase1 is ROS-dependent [

24]. In a positive feedback loop, IL-1β promotes intracellular accumulation of ROS by uncoupling antioxidant enzyme, especially SOD. This stance partially supports the current study, in which relative higher

NLRP3 accompanied by increased

caspase 1 and

IL-1β in 10% WB may lead to suppressed

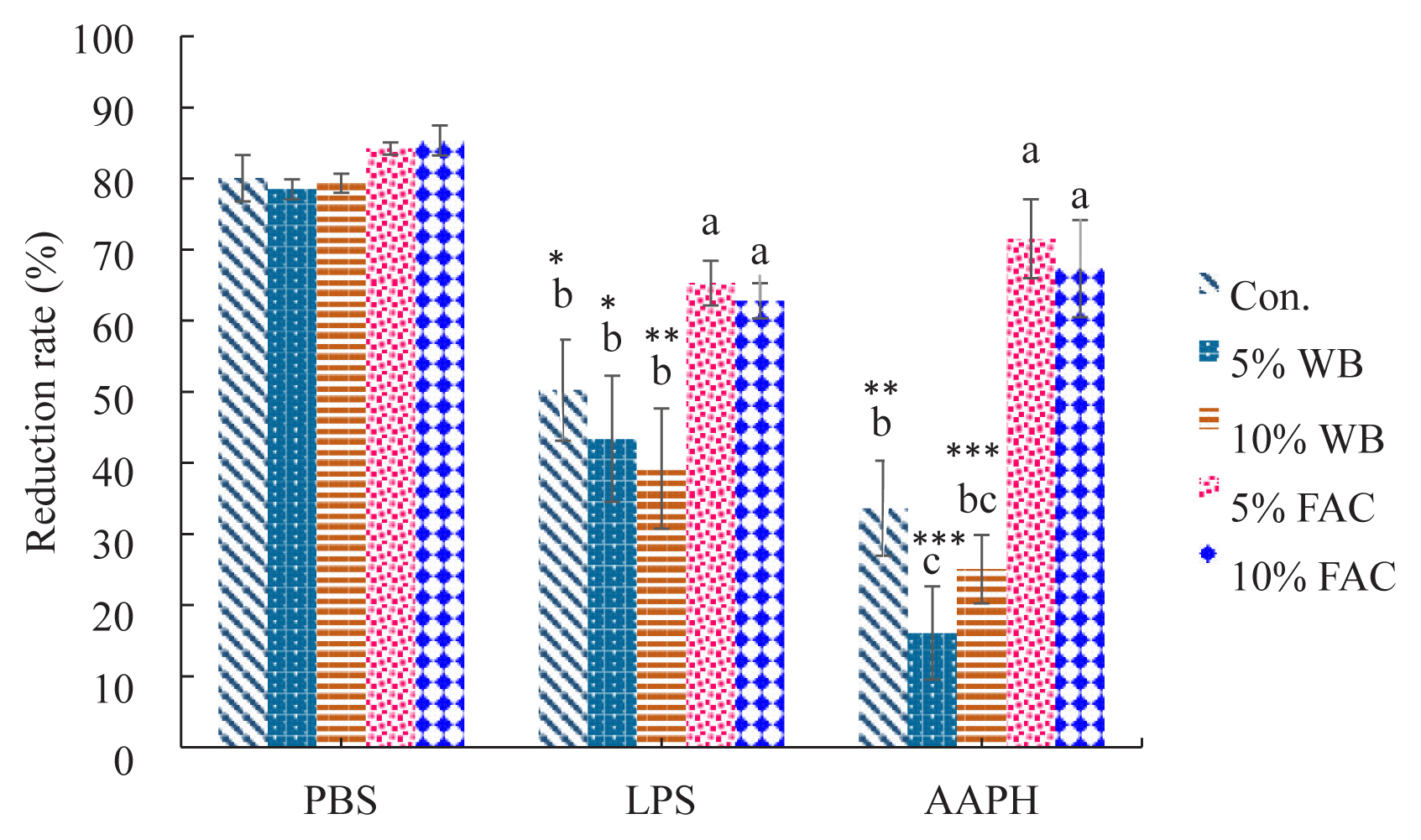

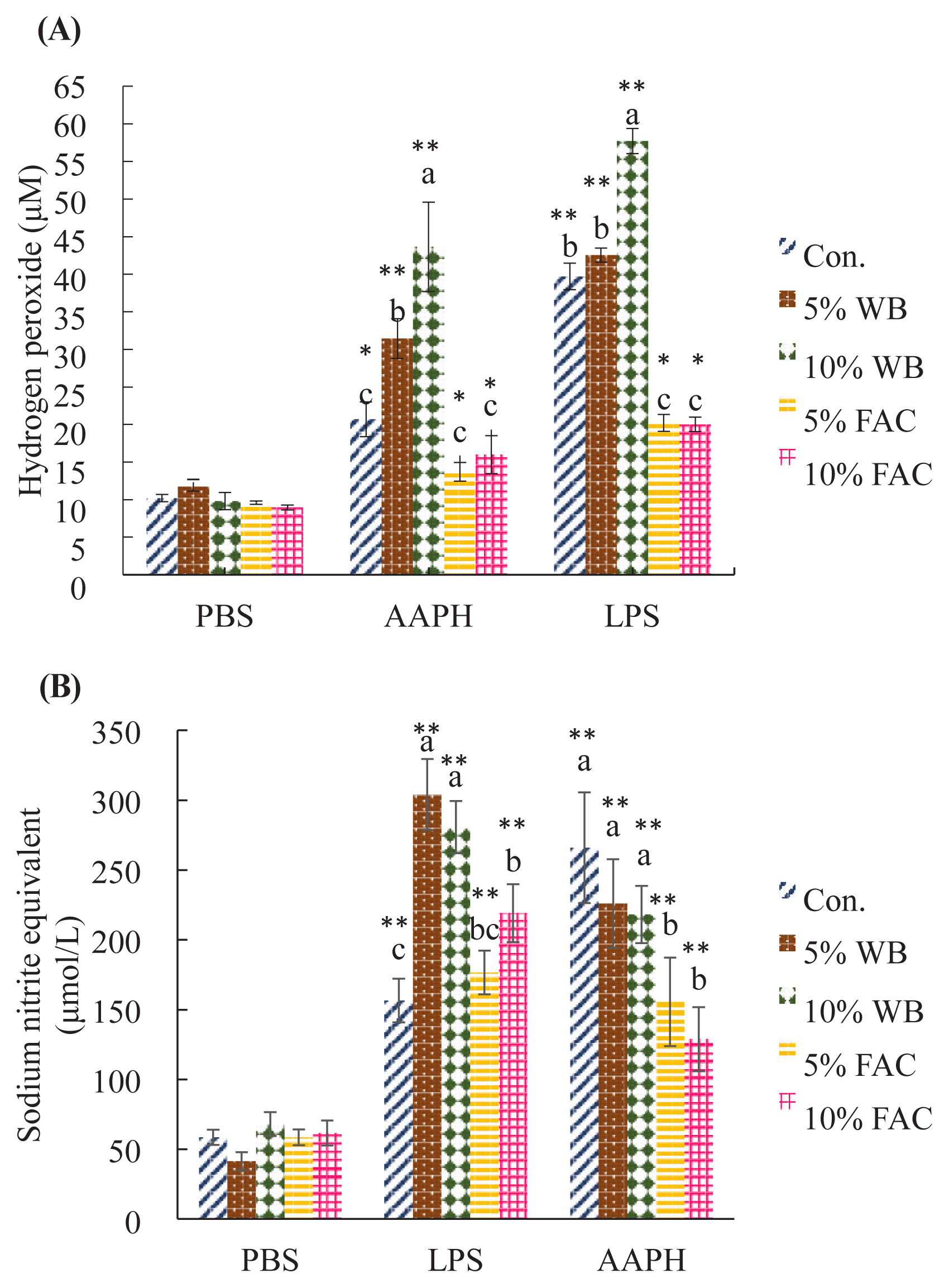

SOD; whilst, cells which were isolated from chickens received 10% WB diet were susceptible to extracellular challenge in terms of higher H

2O

2 and NO production may also buttress the above standpoint. NO is a product from three types of NOS; however, apart from two of them constitutively expressed, iNOS only expressed upon cell activation [

25]. Our study showed that as being stimulated by AAPH and LPS, which are responsible for inducing free radical and activating inflammation, H

2O

2 was increased especially in 10% WB group, followed by 5% WB; and despite not completely consistent NO level, chickens received FAC in diet showed relatively low NO production after extracellular stimulation. It was reported that the fate of cell depends on the balance between activities of classes of gene, including those encoding for the expression of inflammatory related molecules (such as interleukin, NO, and PGE

2) [

26], higher cell viability observed in FAC inclusion groups may thus further support the results of gene and protein expression level.

In another manuscript, fatty acid profile in meat indicated that FAC supplementation may increase the ratio of monounsaturated and saturated fatty acids. This may result from the up-regulated genes for enzymes involved in FA synthesis (

Figure 1C), in which FAS and FADS2 were expressed in equal high level. FAS plays a central role in

de novo lipogenesis in animal body, and FADS2 is responsible for be a rate limiting step in

de novo long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids synthesis [

27]; these support the results found in fatty acid composition in chicken muscle. Moreover, it was reported that different diet can alter the expression of PPARs in broiler livers [

28], and as the expression of PPARα increased, fatty acid β-oxidation would be enhanced [

29]. These could attribute to the repressed triglyceride (TG) level in chickens receiving FAC in diet. Moreover, since cholesterol synthesis is a highly regulated pathway subjecting to transcriptional modulation, the decreased TG level that is indirectly correlated to the cholesterol and high density lipoprotein metabolism was thus hypothized to be attributed to not only PPARα, but also the suppressed HMGCoAR regulating cholesterol synthesis and the indirect stimulation of LPL expression [

6]. Several studies found that polyphenols were able to suppressed cholesterol synthesis through inhibition of HMGCoAR expression [

30]. It’s noteworthy that the lipid-regulation mechanism of types of polyphenol in AC hasn’t yet to be studied, suggesting a new sphere worthy to be developed.

It was reported that activated PPARα is capable of repress ing inflammatory genes, such as caspase, COX2 and IL-6, by promoting the cytoplasmic inhibitor of NF-κB, thus suppressing NF-κB entering nucleus to activate downstream molecules [

31]. For those NF-κB related inflammatory genes, they indeed showed approximately opposite pattern with PPARα, FAS, and ACC. However, it’s interesting to find that in our study, PPARα, FAS, and ACC were expressed in similar pattern with antioxidant genes regulated by Nrf2. These seem to be associated with the indirectly antioxidant action of PPARα by upregulation of SOD, CAT, HO-1, and even GSH-related genes and inhibit NADPH oxidase (

NOX) gene activation and consequently ROS generation [

24]. Furthermore, results in present study seem to in line with previous study demonstrating that augmentation of PPARα could increase HO-1 and decrease caspase expression [

31]. Since PPARα, similar to Nrf2 and NF-κB, is highly sensitive to redox perturbations [

6], and that it’s important to solve oxidative stress and to improve lipid profile in chicken meat [

32].

In conclusion, our study addresses possible interplay among oxidative, inflammatory, and lipid metabolism pathways in broiler chickens through WB and FAC. Dietary supplementation of wheat bran promoted the activation of molecules involved in NF-κB pathways in chickens at gene level, which further supported by relatively high NF-κB protein ratio in nucleus. Meanwhile, chickens with FAC rather showed opposite results in terms of relatively higher expression of Nrf2 antioxidant pathways. The improved defense mechanisms summarized above are in line with suppressed H

2O

2 and NO production, and even cell viability challenged by extracellular reagents. Moreover, increased expression of lipid-related genes like PPARα, FAS, and FADS2; and inhibited HMGCoAR buttress better FA saturated-ratio and serum lipid parameters in FAC groups in our separated manuscript. These lipid-regulation are promising links with Nrf2 and NF-κB regulatory pathways in terms of similar patterns of expression in Nrf2 regulated genes and approximately opposite pattern with NF-κB related inflammatory genes. The above findings demonstrate potential molecular targets to dissect ROS-related complications in broiler chickens, and to develop strategies to manipulate the balance among Nrf2, NF-κB, and PPARα responses under specific conditions in modern rearing environment (

Figure 6).

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print